African Bowhunting

the theory and the practice

Compiled by Harry Marx

6thEdition

Revision 2015/06/01

This book is a comprehensive look at the theory of bowhunting,

and how it affects the practice thereof.

It is also used by the South African Bowhunter's Association for its

Bowhunter Proficiency Certification (BProC) program.

In this introduction to bowhunting the focus is on the theory, practice, reasons and larger picture for the curriculum. |

This project has now been running since 2009, and now we are presenting the 6th edition.

In the 3rd, the major change moved away from categorising animals and define requirements in relation to animal weight directly.

In the 4th we made changes and simplified the assessment of required penetration.

In the 5th, we revisited this theory, and made an incredible break through. Assessing required power is now based on three simple graphs. We also define a new unit for this, which works much easier.

In the 6th edition we revised the whole book, and added e few subjects.

|

1 Foreword

|

2 Introduction

|

2.1 Why Bowhunt?

Bowhunting can be easy, or very difficult, as you choose. Sitting in a hide, you only need to have lots of patience. Hunting by "walking and stalking", with a bow however, can be very challenging. You need to get very close to the animal, and then draw the bow, and shoot, without being seen. |

2.2 Is "minimum requirements" for hunting sensible?

Before we can discuss the theory of penetration, we need to make a judgment call on a more fundamental issue - when do we consider penetration as "enough"? In other words, when do we consider an arrow that hit its target, as lethal? This sounds rather strange, since we all know exactly when an animal is dead or not. The question we are posing is of a slightly different nature. Yes, we know whether a particular animal is dead, but we need to determine when it would have died, before we make the shot! Hindsight is not allowed. |

Clearly, there are people that survive even severe overdoses. Likewise in hunting, we would like to apply an arrow that in "most" cases, results in a quick kill. |

3 In Theory

3.1 Penetration Ability

|

| Further Reading: Koert Pretorius, AB, Nov/Dec 2000, p19, "Jumping the string" |

|

|

|

Bradly Hunt from Alkali International, published an article on AmmoGuide.COM called A New Concept in Deep Penetration of Solid Rifle Bullets in Large Animals. He describes a penetration index used in the big game hunting community where PA equals the square root of Kinetic Energy X Sectional Density / Frontal Area.

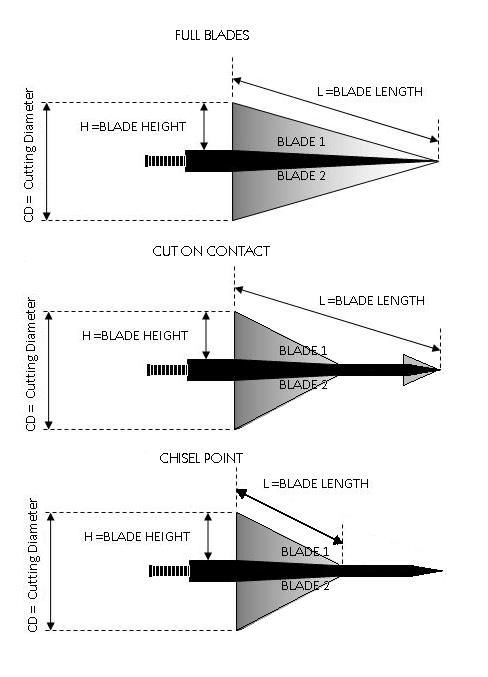

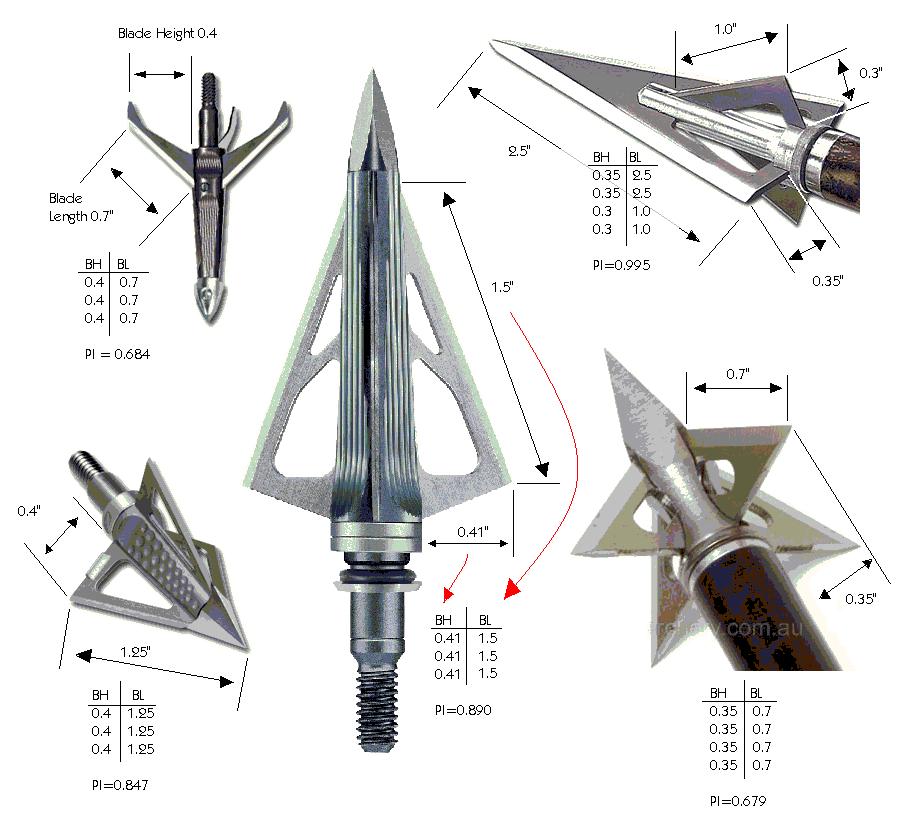

In an effort to quantify all these measurements on the broadhead, Dr. Ashby suggests the use of a tissue penetration index ( TPI = length/(BladeCount x Cutting diameter/2) ). This index captures most of the listed attributes, but excludes the effect of the general size of the hunting point (see next table). It also fails to provide for modern multi-blade hunting points with so called "bleeder blades." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Further Reading: Cleve Cheney, AB, Jan/Feb 2001, p24, "Arrow penetration - Is there more to it than kinetic energy and momentum?" |

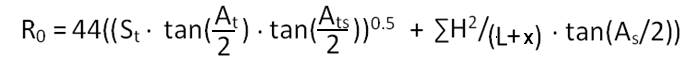

3.1.1 Penetration Index - A new formula

|

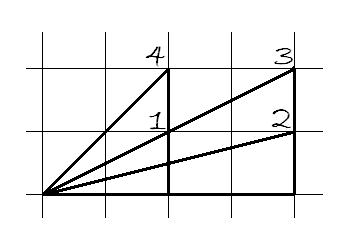

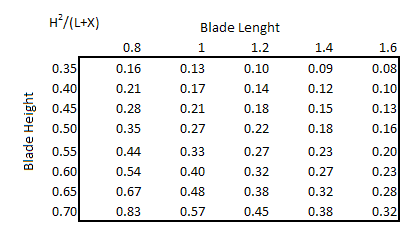

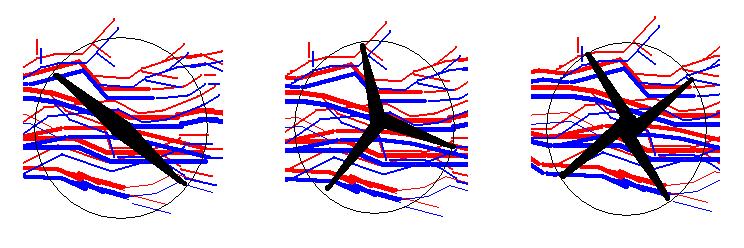

Changing blades profile from #1 to #2, you would expect the force needed to cut flesh to be half as much, from #1 to #3, it should double, and from #3 to #4 it should also about double (or be about 4x that of #1). Using the relationship of H.tan(A/2), which is the same as H2/(L+x), where x is the length of the blade along the shaft, we can see this pattern, except for #4, which results in just more than 3.5x the force needed than for #1. For our purposes it will suffice. |

If you look at the table above (made with the tan(A/2) principle), you will see that increasing the blade length (changing from blade #1 to blade #2 as in the above picture), reduces the force needed to cut (going right on any row). I.e. double the blade length, and the force needed is halved. |

Blades CD L CD(mm) L(mm) H(mm) TPI H2/(L+x) The first 3 rows increase the cutting diameter. The new factor is slightly more critical of cutting diameter than TPI. 2 1 1 25.4 25.4 8.9 1.00 1.00 2 1.25 1 31.75 25.4 12.1 0.80 0.71 2 1.5 1 38.1 25.4 15.2 0.67 0.54 |

|

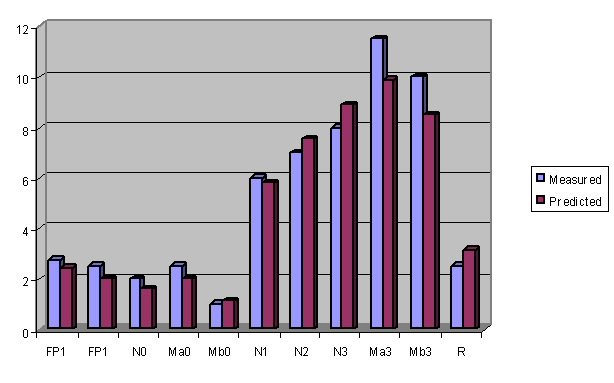

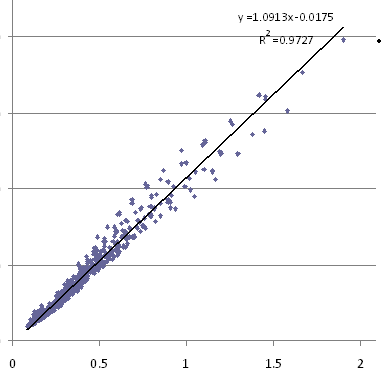

This equation predicts how much resistance a broadhead of a particular design will experience when pushed through muscle tissue very slowly. The graph on the left is of predictions compared to actual measurements. This was for 2 different fieldpoints, a Nitron with no blades, a chisel point mechanical with no blades, a cut-on-contact mechanical with no blades, a Nitron with 1,2 and 3 blades, the mechanical with chisel tip and 3 blades, the c-o-c mechanic with its blades, and lastly a Razor Back: a two (fixed) bladed c-o-c broadhead. |

|

Here is the function developed in vbScript for among other applications, MicroSoft Excel: |

Function PDepth( _

ByVal Ro As Double, _

ByVal m As Double, _

ByVal v As Double, _

ByVal dia As Double, _

ByVal a As Double, _

ByVal ds As Double, _

ByVal c1 As Double, _

ByVal c2 As Double, _

ByVal c3 As Double, _

ByVal KELoss1 As Double, _

ByVal BodyDepth As Double, _

ByVal KELoss2 As Double)

Dim s As Double, d As Double, PI As Double, KE As Double, vv As Double

PDepth = "err"

PI = 3.141592654

s = 0 'initialize distance penetrated

If Ro < 2 Then Exit Function 'too little Ro, model will crash

If ds <= 0 Then ds = 0.001 '1 mm steps

'limits the minimum speed to about 140 fps

v = v - ((c1 / v) ^ c2 - 1)

If v < 0 Then Exit Function

'SI units

Ro = Ro / 2.2 * 9.8 'lbs to Newton

m = m * 0.065 / 1000 'grains to kilogram

v = v * 12 * 2.54 / 100 'fps to meter per second

dia = PI * dia * 2.54 / 100 'shaft dia in inches to shaft area in

'meter squared per meter shaft

a = a / 1550.0031 'inches squared to meter squared

BodyDepth = BodyDepth * 2.54 / 100 'inches to m

KELoss1 = KELoss1 * 1.359431604 'foot pounds to J

KELoss2 = KELoss2 * 1.359431604 'foot pounds to J

If KELoss1 > 0 Then 'modeling bone penetration as loss of energy

' this is valid as penetration into bone is related to KE

KE = m * v ^ 2 / 2

KE = KE - KELoss1

If KE < 0 Then Exit Function 'if we don't get through the bone - done

v = (KE * 2 / m) ^ 0.5 'get the speed exiting at back of bone

End If

vv = v ^ 2 'meter per second squared - we will loop using vv

s = 0

Dim aa As Double

Do While vv > 1 And s < 10

If s > BodyDepth + 0.75 Then ' [ ] ------------->

Ro = 0

a = 0

aa = 0

PDepth = 999

Exit Function

ElseIf s > BodyDepth And s > 0.75 Then ' [ ----]------->

aa = (0.75 - (s - BodyDepth)) * dia

a = 0

Ro = 0

ElseIf s > BodyDepth Then ' --[-------]--->

aa = BodyDepth * dia

a = 0

Ro = 0

If KELoss2 > 0 Then ''exit rib breakage energy loss

KE = m * vv / 2 - KELoss2

'if we don't get through the bone, done

If KE < 0 Then exit do ' --[-------]

vv = (KE * 2 / m)

KELoss2 = 0

End If

ElseIf s > 0.75 Then ' [ ------------> ]

aa = 0.75 * dia

Else ' ------[----> ]

aa = s * dia

End If

d = (Ro + (Ro * a + aa) * vv) / m

vv = vv - 2 * d * ds

s = s + ds

Loop

If s >= 10 Then

PDepth = 999

Else

PDepth = s * 100 / 2.54 'and return the result in inches

End If

End Function

|

A similar model was previously used by the author to predict the trajectory of an arrow through the air, based on this same friction principle. The friction (Fr) the arrow experiences at various speeds changes, so it also changes as the arrow decelerates during penetration. This model involved simulating the arrow’s path in small steps, and to calculate the friction at each step. But it requires a "friction constant" (k). For the trajectory we could calculate k using two measurements, at 1Y and 20Y, and adjusting k until it predicted the same speeds as measured. |

Speed loss for breaking rib on entry: (20 foot-pounds loss)

300 500 700

200 -100 -52 -35 As you can see, slower and lighter

225 -81 -44 -31 arrows looses more speed breaking

250 -70 -39 -27 ribs than faster and heaver ones.

275 -61 -35 -24

300 -55 -32 -22

|

For the purpose to standardize energy loss and penetration, we propose the kinetic energy loss (foot ponds) be calculated as the animals weight (in kg) raised to the power of 0.28, multiplied with 6.24.

This is not magic numbers, but rather an aggreement. |

Approximation of energy needed to break a rib per animal mass:

Animal energy

weight needed

10 12

50 19

220 29

1060 45

5000 70

|

Another interesting prediction we see is: when we take two arrows, weighting 900gr @ 200fps and 300gr @ 345 fps (both have kinetic energy 80 ft.lbs) and say both break a 25 footpound rib on entry, the 900gr arrow looses 18% of its penetration, and the 300gr arrow only 13.4%. However, the 900gr arrow still out penetrates the 300gr one by more than 50%. |

But we are now loosing focus and are trying to define penetration in terms of the target being hit, and not the broadhead. Although this is the reality of hunting, the heterogeneity and all variables of a live animal being penetrated by an arrow, is totally impossible to predict. Instead we limit ourselves to muscle tissue, and the effect of a single rib on entry and exit. In other words, we standardize the animal. |

Warning: Although tests like these try to prove heavier arrows have more penetration, they rather reflect that the bow is slightly more efficient at higher arrow weights. The medium is not comparable to wet tissue, but is indicative of penetration into bone. |

| Further Reading: Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Apr 2007, p27, "What is TPI?" |

3.1.2 A Case Study on Friction

According to tribology (the scientific study of friction):

|

Animals consist of a mixture of solids (bone), elastics (hide, sinew, muscle) and liquids (water and oils). Fats are "oil-lubricated solids". So perhaps it’s best if we look at lubricated hard surfaces and fluids. So for liquids, to the best approximation, the arrow feels friction relative to its speed squared. |

Now, lets look at all the attributes of these arrows closely:

gr Dia. Spine gpi FOC Fc% fps KE cP

Gold Tip 370 0.295 400 8.5 11 44 192 70 48

Easton 422 0.294 340 10.5 9.6 53 277 72 52

CarbExp 458 0.315 350 11.8 8.9 52 268 73 55

|

Fc% is the critical loading weight of the arrow as a percentage of the bow’s draw weight, and is an indication of dynamic spine - values between 38% and 45% is generally good (45 being the stiffest). (The definition of these attributes is discussed later in full detail.) KE is kinetic energy and cP is the momentum x100. So how can we explain the above anomaly, where both KE and cP is largest for the Carbon Express arrow, but it penetrated the least? |

Have a look at these values:

Dia cP Frontal Area cP density

Gold Tip 0.295 48 0.068 7.022

Easton 0.294 52 0.068 7.651

CarbExp 0.315 55 0.078 6.996

|

If we now look at the cP density, it explains why the Easton did the best. If we took the FOC and dynamic spine into account, it also explains why the GoldTip did 2nd best. But, these experiments were done in a cardboard box butt. What effect would this have had? |

The tribologists would be tempted to say that since the friction area’s were dry, the pressure on the bigger shafts was more and faster speeds had slightly less friction, and so the Easton won. They would also claim that if hunters shoot at flesh, friction is independent of surface pressure, but goes up with speed squared. So in flesh, the Carbon Express would have won. |

3.1.3 Front of Center

Other factors influencing penetration of projectiles are sectional density and the centre of gravity of the arrow (FOC). Sectional density is the mass of an object divided with it frontal surface area. Sectional density does play a major role in arrow penetration, since the difference in arrow shaft weight. However, the differences in diameter are usually very small. However, new technology are decreasing arrow diameter, and this will need to be revised. |

|

Where it plays a role in penetration is easiest to picture if an arrow is imagined that hits a target slightly at an angle. Such an arrow's momentum, acting through its centre of gravity, will push the point sideways and greatly reduce penetration. For this reason a higher FOC makes the bowhunter's set-up more forgiving for a slightly less than perfect arrow flight. This is in fact the same reason an immediate unease was felt about using a spear to hunt an elephant, as described elsewhere. |

|

|

|

|

|

We can provide an empirical formula for his results, and it looks like this:

If you are wondering what an arrow's FOC will be, but have not yet built it, you can use the following equation to calculate it:  where Wt is the total arrow weight, Wi is the weight of each component, L is the length of the arrow, and Li is the distance of the component's center of gravity from the nock point. |

| Further Reading: Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Apr 2008, p30, "FOC - Front of centre balance" JP de Villiers, AB&A, Feb 2008, p58, "FAQ's" Dave Holt, AB, Nov/Dec 2000, p7, "Arrows - Heavy versus light" Dave Holt, AB, Mar/Apr 2001, p9, "The Downrange decay of Arrow Velocity" Herman Brand, AB&A, Dec 2007, p51, "Swaar of Ligte Jagpyle?" |

3.1.4 Shaft Diameter

The shaft of the arrow experiences friction during penetration, and as such affects it. Experimental results have shown that an additional factor can be multiplied with the achieved velocity or momentum, to accommodate this influence. This shaft factor is based on whether the shaft of the arrow is the same size or larger than the hunting point's ferrule's diameter. If the arrow's shaft is the same size, a shaft factor of 0.9 should be used, while if the arrow shaft is larger, a value of 0.6 should be used (if smaller 1.0). |

3.1.5 Shaft Tilt

The model we are trying to develop has at its hart defining penetration in terms of the arrow's attributes. But some of these attributes are not independent of the target, for example the Ro defined elsewhere, which is a function of the blade design and the type of material being penetrated. As such, we had to standardize on some sensible medium. In looking at the effect of arrow tilt, we are delving into even harder ground. |

Wp x Lf + Wgpi x Lf x Lf/2 + Wgpi x Lb x Lb/2 + 40 x (Lb - 3) |

where Lf is the length of the shaft in front of the COG, |

The deeper the arrow penetrates the more of the shaft is in contact with the target. This means the tilting increases as the arrow penetrates and the influence of the tilting increases. Another big problem with trying to quantify this effect is that the size of the force that does the tilting, is dependent on the medium shot into. So we sit with an initial tilt caused by wind (a variable independent of arrow design), and the force (a second independent variable), while we are trying to define a model based on only the arrow. |

3.1.6 Putting it all together

Either one starts by measuring the penetration resistance (Ro) (the easiest but the least precise), or one measures the dimensions of the broadhead, and calculate it using the formula for Ro (more complicated, but a bit more precise). |

Mass Body width

(kg) (inches)

10 4

100 12

220 17

800 31

5000 74

|

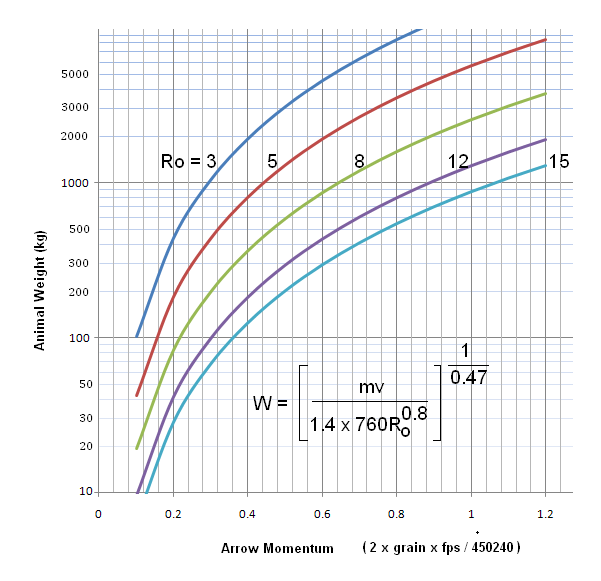

Now if you think the model is complicated, the mathematics actually simplifies to where more than 95% of the model can explained by: |

weight x speed

Penetration = ------------------

760 x Ro0.8

|

Penetration Graph: |

In this graph we have for different resistance values, the approximate momentum required for a full body penetration, not hitting any bones. |

Remember, we are not really concerned with the width of the channel here, since it was agreed that all broadhead wound channels exceeds the 7.5mm proven to be fatal within 10 seconds. |

3.1.7 Required Penetration Depth

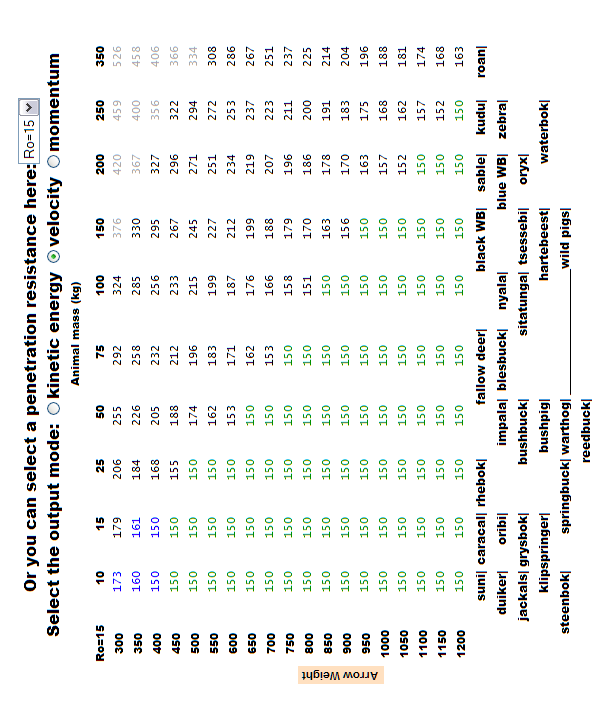

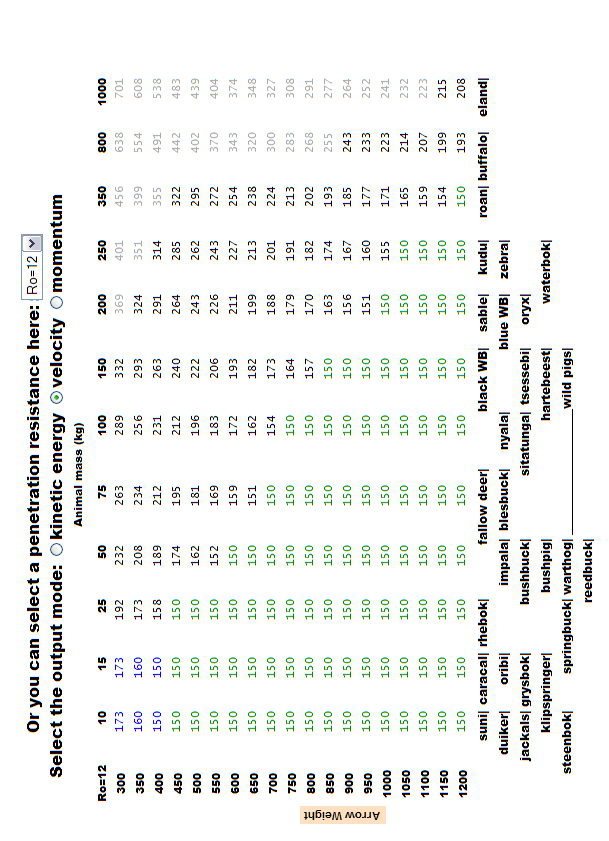

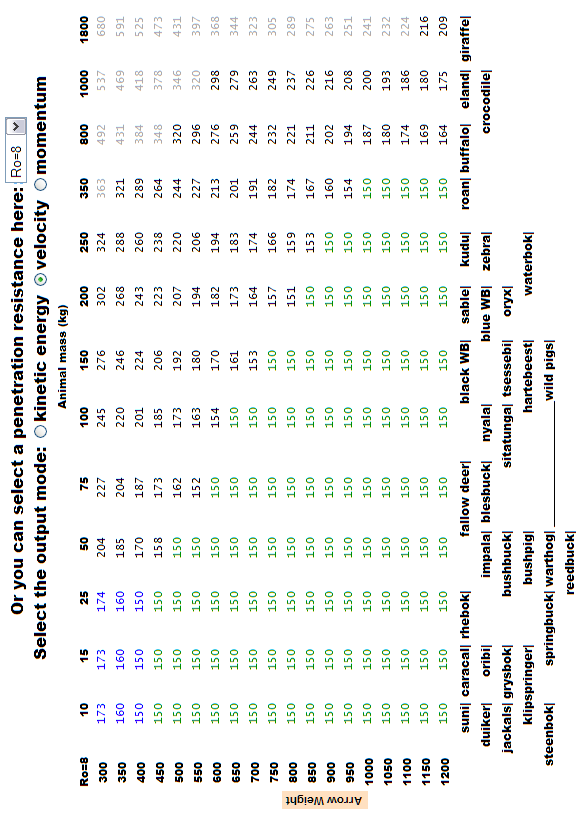

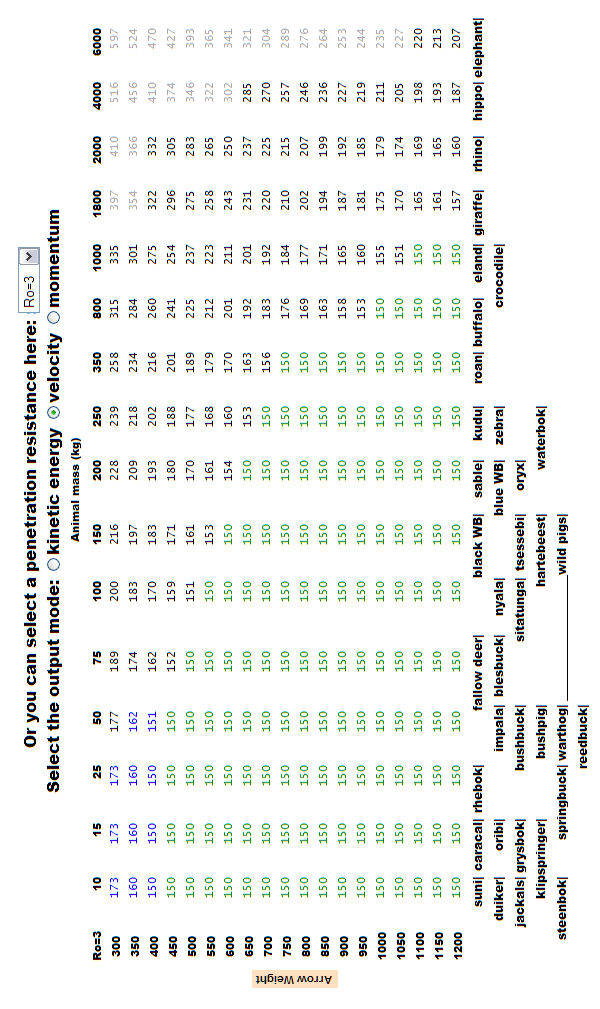

On http://www.bowhunting.co.za/SABA/asp/minreq.asp, the whole model is implimented.

On it you can select the broadhead that closest represents your broadhead, and the web page will show

you what the required kinetic energy, momentum or speed is, for the particular animal and arrow weight. |

The final product is one where you can with a single selection of the broadhead determine the suggested minimum requirements for all arrow weights, and all animals. The answer is then presented in a simple lookup table. Of course there are always incidental factors that will cause deviations, and some animals bend the rule. The fine print therefore reads that "your experience may vary" simply because the average bowhunter is looking at a relative few hunts per year. Indeed, the variability of penetration cannot be wished away. And of course, the result is not precise. You simply cannot measure any of the parameters with precision, and the result cannot be precise. We suggest you expect about a 10% error, for ex. if a value of 53 foot-pounds are calculated, you can assume it is accurate to about ±5 foot-pounds (=53/10). The only counter we suggest to incidental factors and imprecision is "overkill' - literary.

|

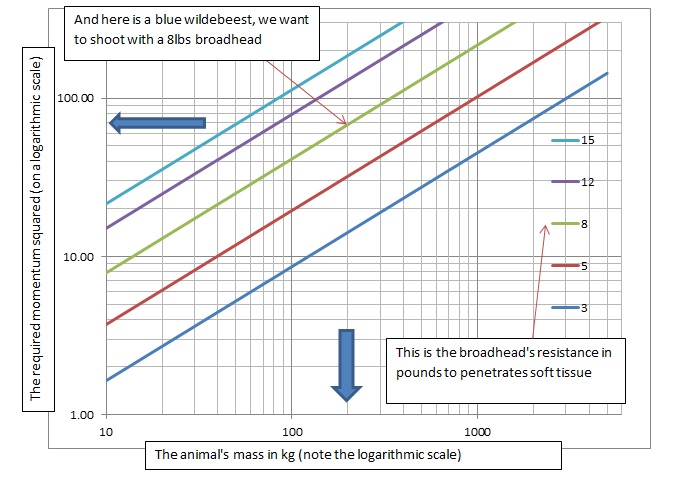

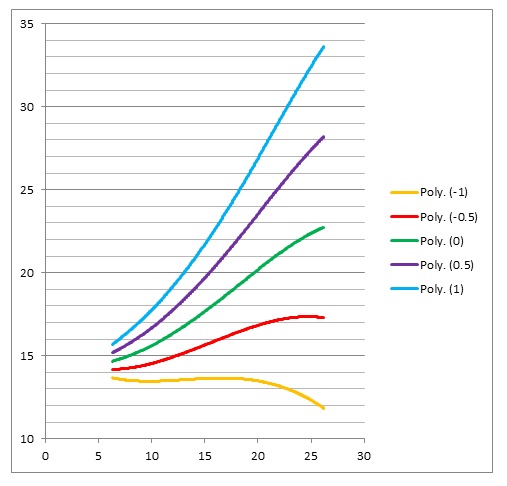

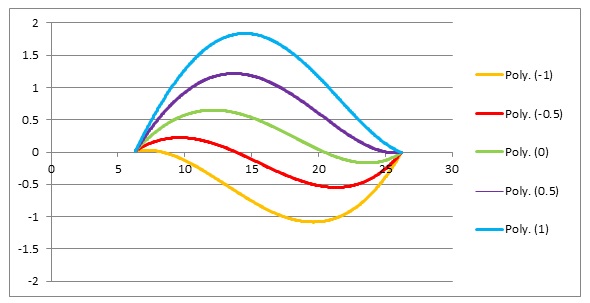

3.1.8 New development - easier to understand graphs

As things are, things change. This sounds like zen, but unfortunately, true. As part of defining the Norms and Standards for hunting in South Africa, the goverment asked us a 2nd time for input in this regard. It was then that we realized that we will first have to do more mathematics, in order for the hunter to do even less... |

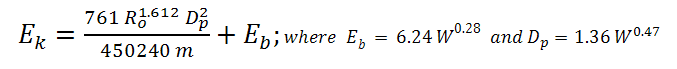

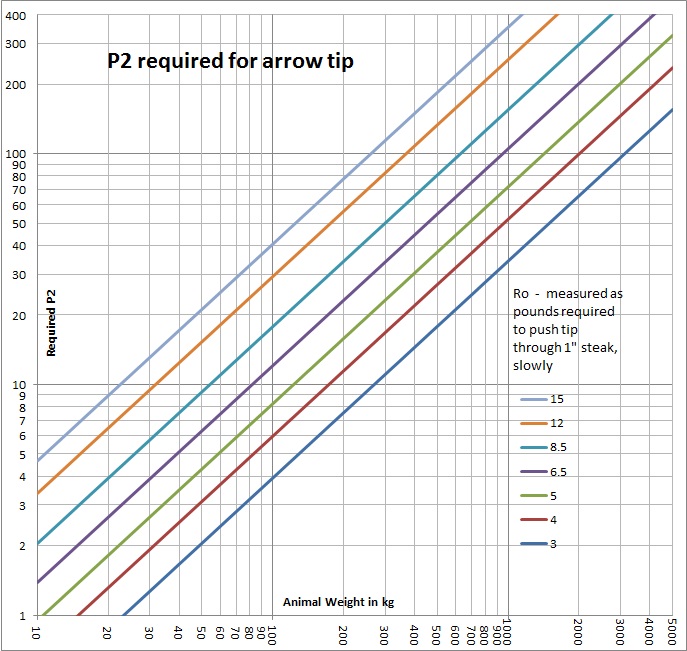

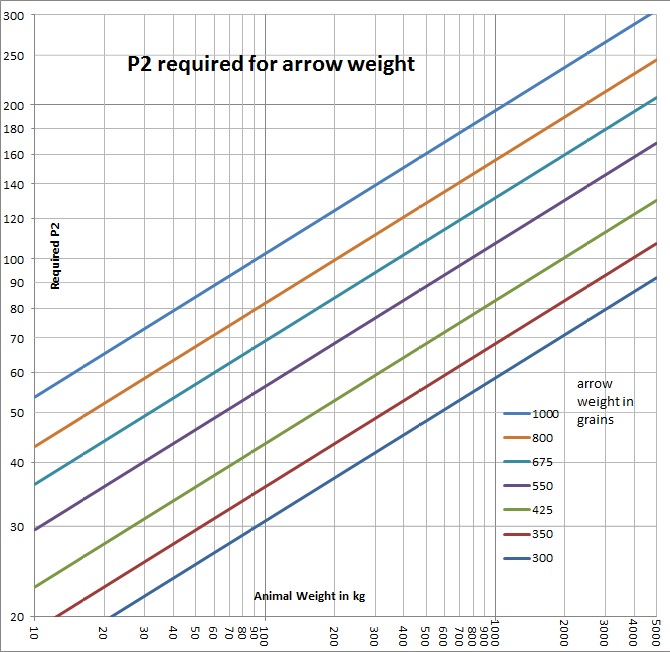

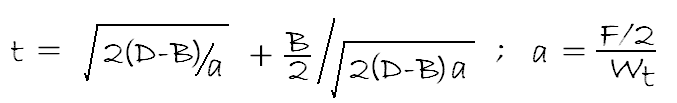

Indeed, this formula is MUCH more interesting, firstly because it defines minimum requirements as the sum of two factors. The 1st factor relates only the broadhead's design to the animal's weight, and the 2nd factor relates only the arrow's weight to the animal's weight. In affect we are able herewith to define the influence of the broadhead independently of the arrow weight, with the provision we work in required momentum squared (P2). |

Relating broad head design to animal weight.

Relating the broadhead's cutting resistance to animal weight. Please note that the values on the axis, is not linear, they are so called logarithmic. Therefore the markers indicate 10, 20, 30 up to 100kg, then 100, 200, 300 up to 1000kg.

|

Relating arrow's weight to animal weight.

|

Does it make sense?

|

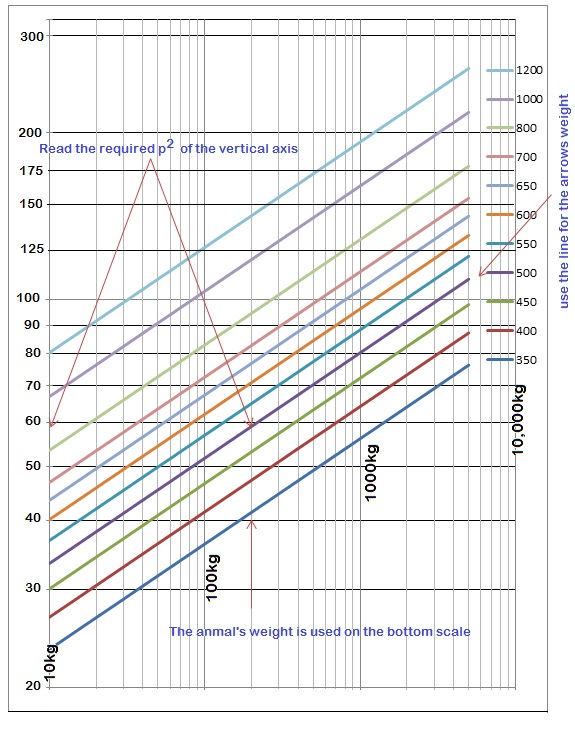

Graph 1. P2 required in relation to arrow tip:

Graph 2. P2 required in relation to arrow weight:

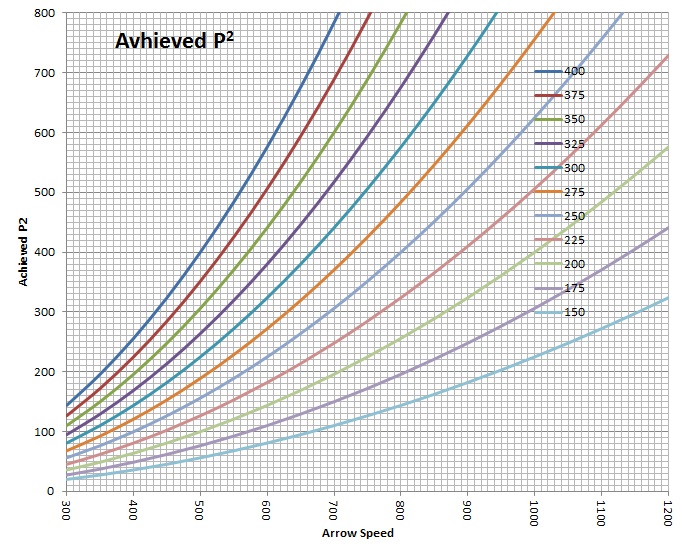

Graph 3. P2 achieved by arrow:

3.1.9 Checking your bow's performance

The next three tables allow you to do all we discussed in this book so far, in three simple steps. Of course you need to know the arrow's weight (in grains), how fast your bow shoots it (in fps), the intended hunting tip's resistance to penetration (in pounds), and the weight of the animal you intend to hunt (in kg). |

3.1.10 The Proof - testing the model

Using these tables in the previous section, we investigated a NAP Nitron with three fixed blades, needing around 8 pounds of force pushing it to penetrate into rump muscle. If you have arrows weighing 700 grains, and you want to hunt blue wildebeest (which tops out at around 200 kg), the new model suggest you need at least 120 sqr.slugs, or 40 foot-pounds. Note, this being here the minimum requirement.

|

| Further Reading: Herman Brand, AB&A, Mar 2007, p30, "Die pyl in pyl en boog" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Dec 2007, p56, "Pyle maak 'n groot verskil" |

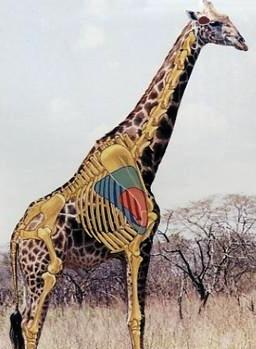

The author(left) with his giraffe... |

3.2 Bow Efficiency

Bow efficiency is the ratio of the arrow's kinetic energy, to the energy used to pull the bow. To determine the energy used to pull the bow, you need a bow-scale. With this you can draw what's called the draw-force curve. It is basically how hard you need to draw the bow, at each particular point in the draw. So what you do is to measure the draw force for the bow at every inch as you draw it. The sum of all these measurements is the draw energy in inch-pounds, which when divided with 12, gives foot-pounds. |

The best way in which to compare bows in relation to efficiency, using this last equation, is to calculate the speed that the bows would shoot the particular arrow you plan to hunt with. The bow which attain the highest speed would of course be the most efficient. By the way, I am assuming these bows are all of the same poundage, and draw length. |

| Further Reading: Harry Marx, AB&A, Nov 2008, p30, "Comparing Bows with bows: virtual mass" Herman Brand, AB&A, Nov 2006, pi, "Beste Boog?" Dieter Noli, AB&A, Nov 2006, p59, "Bow evaluation methods" Rean Steenkamp, AB&A, Jun 2006, p43, "Who says a longbow isn't good enough?" |

3.3 Bleeding and Penetration

Finally, we are getting closer to the actual hunt... |

|

As bleeding rate is sometimes likened to the result of the surface area of the cut, it would seem logical to use as many as possible blades. However, it is not flesh that bleeds, but arteries. And no matter how many times you cut an artery, it bleeds just as fast as if it was cut once. So arguments and opinions abound - we will look at the facts. |

If you draw a circle with the same diameter as the broadhead's cutting diameter, and in it the cuts made by the broadhead, you can easily see that with 2 bladed broadheads, you can draw many lines representing arteries through the circle that does not get cut. When you do this with a 3 bladed broadhead, the chance of an artery being cut by any blade drastically increases. |

|

For 4 blades the penetration depth would be: |

D0 20"

D2 (penetration) ACA (average cutting area)

inches square inches

2x 3x 4x 2x 3x 4x

10 8.0 6.7 6.3 6.6 6.0

11 9.0 7.6 6.9 7.5 6.8

12 10.0 8.6 7.6 8.3 7.7

13 11.1 9.6 8.2 9.2 8.7

14 12.2 10.8 8.8 10.1 9.7

15 13.3 12.0 9.5 11.1 10.8

16 14.5 13.3 10.1 12.1 12.0

17 15.8 14.8 10.7 13.1 13.3

18 17.1 16.4 11.3 14.2 14.7

19 18.5 18.1 12.0 15.4 16.3

|

In this table we can see that for example in row 3, if a field point penetrates 20", and a 2 blader 12", then a 3 blader will penetrate 10", and 4x only 8.6". Their cutting areas will be 7.6sq", 8.3sq", and 7.7sq". |

|

|

Which is basically common sense isn't it?

|

| Further Reading: Herman Brand, AB&A, May 2007, p32, "Minder Bloed" |

3.4 Shooting Distances

3.4.1 ...based on Reaction Time

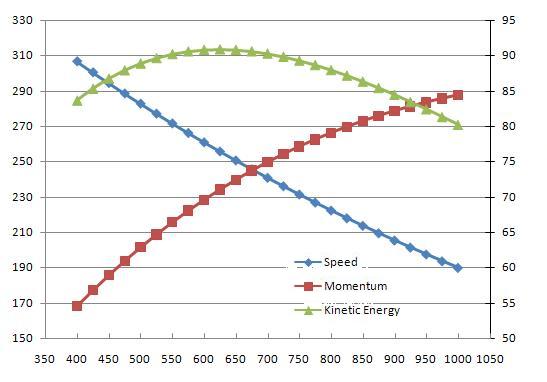

In the past speed was one of the most important factors of a bow as promoted by industry. This of course makes sense if you are selling bows. The IBO standard (being misused as it is) set a constant arrow weight, and allows the buyer to make a rudimentary/superficial comparison between bows. More importantly, it allowed manufactures to advertise "mine’s bigger than yours". The standard could have been defined differently - what is the heaviest arrow the bow will shoot at 200 fps? This (although totally impractical) would have instead led to a weight race... |

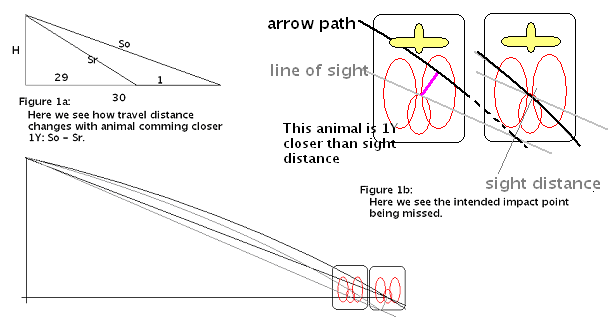

|

Shooting high (+) and low(-), for animals at various distances,

for different arrow speeds, that comes closer 1Y after ranging,

for elevations relative to anchor point +1 to -5Y.

50Y 40Y 30Y 20Y 10Y

150 4.0 to 3.1 3.4 to 2.9 2.6 to 1.9 1.8 to 0.9 1.1 to 0.0

175 3.1 to 2.7 2.5 to 2.0 1.9 to 1.3 1.4 to 0.4 0.9 to -0.3

200 2.4 to 2.0 1.9 to 1.4 1.5 to 0.8 1.1 to 0.2 0.8 to -0.4

225 1.9 to 1.5 1.6 to 1.0 1.2 to 0.5 0.9 to 0.0 0.7 to -0.5

250 1.6 to 1.1 1.3 to 0.8 1.0 to 0.3 0.8 to -0.2 0.6 to -0.6

275 1.3 to 0.9 1.1 to 0.6 0.9 to 0.2 0.7 to -0.3 0.6 to -0.7

300 1.1 to 0.7 0.9 to 0.4 0.7 to 0.1 0.6 to -0.4 0.6 to -0.7

|

|

|

If you take a video recording of an animal being shot with a standard video camera, the frames or still photos it takes, is about 25 per second. This means the frames are 0.04 seconds (40 milliseconds) apart from each other. |

|

If you shoot at an impala at 20Y, with an arrow at 250 fps, the animal has 187 milliseconds to react between the sound reaching it, and the arrow doing so. If you wish to reach the animal before 100 milliseconds, you will have to shoot at 395fps. |

|

Here we see the time (milliseconds) between the sound and arrow reaching the target, the distance the animal can "fall" during string jumping (reacting only after 100ms), and the speed at which it would be falling by this time. Clearly you can see the need for 275+ fps at 30Y and 200+ fps at 20Y, to minimize string jumping. |

Time (milliseconds) Distance (inches) Speed (fps)

50 40 30 20 10 50 40 30 20 10 50 40 30 20 10

150 868 694 521 347 174 114 68 34 12 1 25 19 14 8 3

175 725 580 435 290 145 75 44 22 7 0 20 15 11 6 2

200 618 494 371 247 124 52 30 14 4 0 18 13 7 5 1

225 535 428 321 214 107 37 21 9 3 0 14 10 7 4 0

250 468 374 281 187 94 26 15 6 2 0 12 9 6 3 0

275 413 331 248 165 83 19 10 4 1 0 10 7 5 2 0

300 368 294 221 147 74 14 7 3 0 0 9 6 4 3 0

|

|

|

Another ground for differentiating between for example a spear and an arrow, is the speed of the projectile. The influence of the speed of the projectile on accuracy will be discussed in the following paragraphs. Its influence on penetration is however also critical for a totally different reason than momentum. It ties in with FOC as discussed above. |

|

The importance of a moving target on the penetration of a slow projectile is easily imagined as the moving animal will cause the projectile to slant during impact. This will decrease penetration in exactly the same way as an imperfect trajectory due to a too low FOC. Again, we will only capture this effect as a general guideline, since currently it does not seem sensible to try and quantify it other than as arrow speed. |

|

|

In turn, defining suggested maximum ranges for all categories of bowhunters is also of ethical importance. This ties in perfectly with accuracy as discussed above. The temptation is all too great for trying to suggest a measurement of an archer's accuracy, and therewith provide suggested maximum hunting distances. The reality is however that even if a hunter could accurately hit the target animal's vitals at 80Y, the time for the arrow to reach the animal will be relatively long, and thereby its movement during this time ("string jump") will negate all the care that went into the perfect shot placement. It is generally accepted by bowhunters that about 20Y is the maximum range for small game (and definitely for warthogs as well) at arrow speeds of about 250fps. Larger game are generally slower to move, and 30Y is quite acceptable for the large antelopes. For Giraffe and buffalo, 40Y is not unrealistic. The maximum suggested hunting distance is not a function of the hunter's accuracy, but indeed of the animal's reaction time (and size of vital organs) vs. the speed of the arrow. |

|

Proposed Maximum Yardage based on Reaction Time

Size (kg) 25 50 100 200 400

Reaction Time

(seconds) 0.1 0.14 0.20 0.28 0.40

Arrow Speed Recommended Maximum Distance (yards)

150 6 8 12 16 23

175 7 10 14 20 28

200 8 11 16 23 32

225 9 13 19 26 37

250 11 15 21 30 43

275 12 17 24 34 48

300 14 19 27 38 54

|

Based on the assumption that the animal is alert, using the formula: |

3.4.2 ...based on Grouping size

"Effective range is the ability to place 80% of your arrows in an 8"circle (20 cm)." - Cleve Cheney.

|

|

The proposed maximum yardage based on accuracy is done in relation to the basic unit of a grouping size - its diameter. A grouping with circumference of 10" (measured as suggested later on), has a diameter of 10/3 = 3.3", and when shot at 50Y, an angle of 0.066"/Y, if you are familiar with MOA, arcTan(dia/(Y*36))*60 = 6.3. It implies on for example small game a shot at the furthest 4"/0.066Y, which is 60Y (A quick approximation is 100x4"/MOA). Building a safety factor into it, doubling the grouping size, this distance becomes 30Y. Here is a table with some values: |

approx. mass (kg) 50 75 100 200 400 800

Average vital dia 4" 5" 6" 6" 7" 8" (also approx)

Circumference "/Y Recommended Max Distance* (Y)

24" 0.160 13 16 19 19 22 25

22" 0.147 14 17 20 20 24 27

20" 0.133 15 19 23 23 26 30

18" 0.120 17 21 25 25 29 33

16" 0.107 19 23 28 28 33 38

14" 0.093 21 27 32 32 38 43

12" 0.080 25 31 38 38 44 50

10" 0.066 30 38 45 45 53** 60

8" 0.053 38 47 56 56 66 75

* safety factor=2

** shots at 50Y and beyond are generally not recommended.

|

|

3.4.3 Finding your safe hunting distance - without maths

|

No guessing, and no acceptable wounding rate... |

| Further Reading: Cleve Cheney, AB, Mar/Apr 2001, p13, "Optimum Range - knowing when to shoot" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Jan 2008, p30, "Long shots - why not?" Cleve Cheney & Jan Burger, AB&A, Jan 2007, p39, "Close shooting makes good sense" Engee Potgieter, AB&A, Jul 2007, p52, "Rooibok - die snaarspringkoning" Engee Potgieter, AB&A, Apr 2007, p25, "Bowhunting Bread and Butter" |

3.5 Equipment

3.5.1 Traditional Bows

| Further Reading: Johan Smit, AB&A, Sep 2006, p51, "Traditional bows - stronger than you may believe" Johan Smit, AB&A, Nov 2006, pi, "Watter Traditionele toerusting is reg vir my?" Johan Smit, AB&A, Jun 2006, pi, "Sorg vir jou Tradisionele Boog" Johan Smit, AB&A, Mar 2007, p29, "Tradisionele boog en die spoedmite" Johnny Snyman, AB, Nov/Dec 2000, p28, "Making a Flemish Splice Bowstring" Johnny Snyman, AB, Jan/Feb 2001, p14, "Making a Flemish Splice Bowstring - Part 2" |

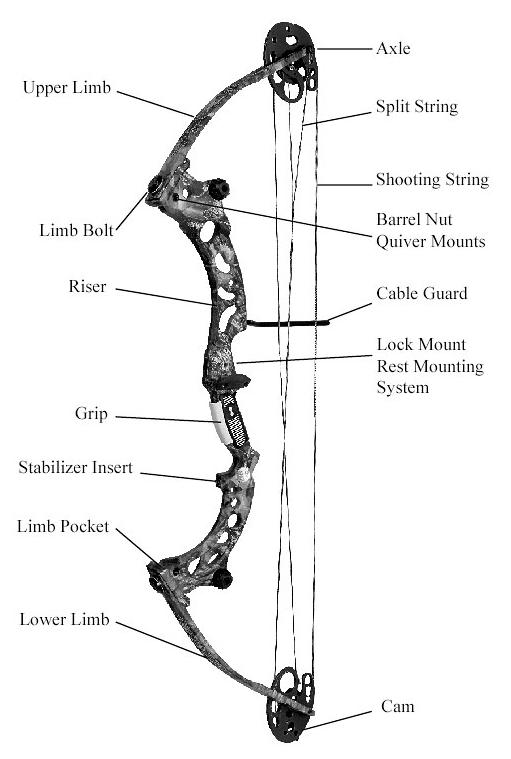

3.5.2 Compound bows

| Further Reading: Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Oct 2007, p51, "Hoe kies ek 'n boog wat my pas?" Herman Brand, AB&A, Nov 2007, p52, "Feite en Opinies" |

3.5.3 Arrow Rests

The very first arrow rest, still in use, is the shelf, or riser of the bow, and against the hand. This works perfectly if your arrows are tuned for the type of rest. The arrow vibrates during release at a particular frequency. When the arrow is released, the string pushes it against the riser, and bends it. This bend initiates a vibration that takes the flights of the arrow out of the way of the riser. Of course, if the arrow vibrates at the wrong frequency, the flights do not clear, and makes contact with the rest. This can cause inconsistent groupings. This is the very reason traditional archers uses feathers for fletching. Feathers are also less rough on the hand. |

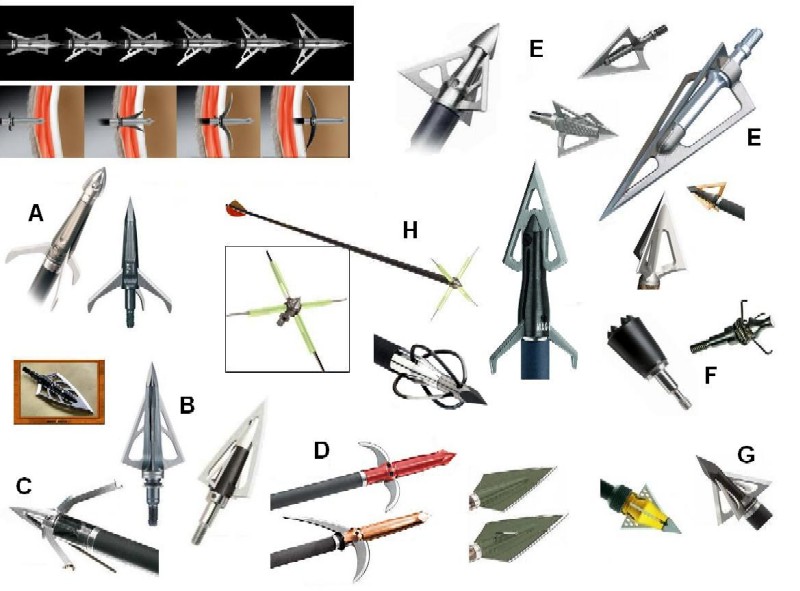

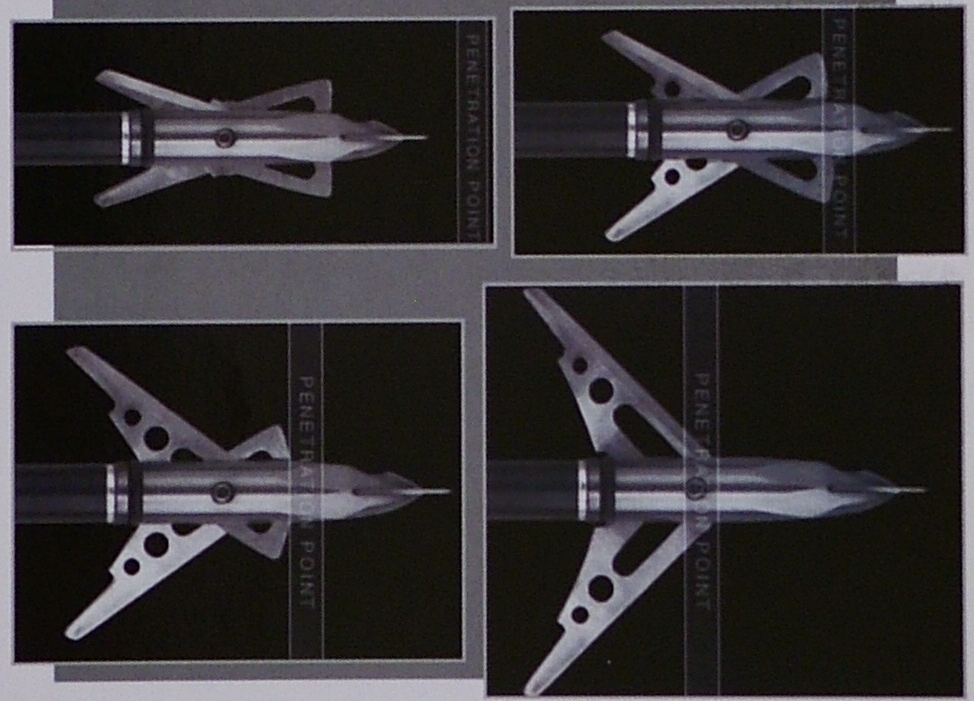

3.5.4 Hunting Points (Broadhead) design

Here's just a small sample of broadheads and variety |

3.5.4.1 Mechanical Points

There are currently 4 types of mechanicals, those that open backwards upon penetrating the skin, those that open by sliding the blades backwards upon skin penetration, opening forwards on contact, and those that open backwards but only after penetrating the full depth of the hunting point's length. |

The first type is the more generally used design, opening backwards. It sometimes causes a small entry wound. It can also be deflected by the opening blades pushing the point away. |

|

3.5.5 Bow Sights and peeps

If you are a traditional shooter, you can skip this section. I won't mind. If you are not, a sight is a useful appendage. There are two major designs, a multi-pin and a single-pin sight. Multi-pin sights are most popular, and has a major advantage. The animal you are hunting will move closer and further, and you will have to change the distance you aim at. With a multi-pin sight you need not adjust any setting, and just shoot on another pin. The drawback it has, is that if you are using really heavy arrows, the trajectory is rather pronounced, and you want to aim at very close to the correct height. If you have set your pins on 10 to 50Y, with 10Y intervals, you will have problems at other distances. My advice to set the pins at 20,25,30,35 and 40Y. You should not hunt at further distances anyway, and closer than 20Y the arrow is traveling fairly straight. I shoot with a single pin sight. The reason is purely personal, I like to aim on the pin, and if the animal is it 37Y, I can set it and shoot. I do not need to aim between pins, something which I'm not very good at. |

You can also spray them with fluorescent paint. A sight light is useful for shooting in low light conditions. Definitely, we are advising you do not shoot late in the evening, unless you have good dogs and lights for the follow up. However, as bowhunters we frequently hide in shades, and shoot at dark coloured animals. |

3.5.6 Broadhead Construction

As a rough estimate, cheap broadheads are not as precisely made as more expensive ones, and the more precisely it's made, the better its aerodynamic properties. Any skew or bent blades will affect the flight path of the arrow, and the effect will increase with increased arrow speed. |

|

3.5.7 Durability

Durability is one of those strange characteristics that are very easy and very difficult to describe. The easy part says it should not break. The difficult one is saying when will it break. In general, most fixed blade broadheads are more robust than mechanical broadheads. |

If it is tough, it doesn't keep the edge so well. One important factor about the steel, if it is too soft, is the edges may not only go blunt easily, but they may even curl around on hitting a rib on entry. This does not only hinders penetration, but also severely diminishes the damage it does. Lung tissue is extremely elastic, and will simply stretch over such a curled edge. This turns your broadhead into a fieldpoint as far as lung tissue is concerned. |

| Further Reading: Sampie Stoffberg, AB&A, Dec 2008, p61, "Die keuse van 'n jagpunt" Engee Potgieter, AB&A, Jul 2008, p15, "What do you expect from a broadhead?" Herman Brand, AB&A, Jul 2008, p61, "Jagpunte ... en jagpunte" Herman Brand, AB&A, Sep 2006, p vii, "Hoe maak mens 'n jaglem bangskerp?" Johan Smit, AB&A, Aug 2006, p ii, "Watter jagpunt is die beste een vir tradisionele boogjag?" Herman Brand, AB&A, Aug 2006, p iv, "Hoe skerp is skerp?" Fritz Rabe, AB&A, Apr 2006, p25, "Hunting the heavies" Dave Holt, AB, Jan/Feb 2001, p7, "Testing broadhead accuracy" |

3.5.8 Arrow stability

There are various factors influencing arrow stability, or how long it takes for an arrow to stabilize after release. In general, longer arrows stabilize quicker, heavier ones slower. But spine, and its center of gravity play major roles. By the way, we assume you have tuned the bow for center shot and straight nock travel. |

3.5.8.1 Static Spine and Dynamic Spine

|

What is true about all arrows is that they bend upon being released. In fact, if you put a static force on the back of the arrow, you'll see the arrow totally collapse at about 20 to 30lbs. Yet, they don't, even when shot in 100lbs bows. The fact is that they actually do collapse, but since they are so quickly out of the bow, they don't get time to bend all the way and break. |

|

For all traditional bows, and most recurve bows, spine plays an immense roll in getting the fletching past the riser, without it touching the riser. The arrow’s stiffness is precisely matched with the bow’s poundage, in order for the first harmonic of oscillations to carry the fletching clear of the riser, as the arrow bends. You can imagine this as if the arrow slithers like a snake around the riser. |

In any case, if the arrow is too stiff, for traditional bows you won’t get flight clearance, and for cut-out risers you’ll get the point of the arrow being pushed up or down. If the arrow is too limb it simply bends too much, and the broadhead will steer the arrow all over the place. Again traditional archers won’t get clearance, since clearance depends on the timing of the arrow bending left and right. For cut-out risers, the arrow will simply steer tail-high or -low, causing porpoising arrow flight, and you can look at paper tuning for more on this problem. |

|

Dynamic spine is affected by the following: |

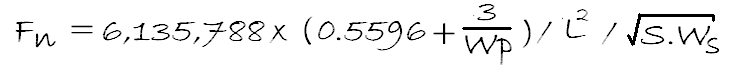

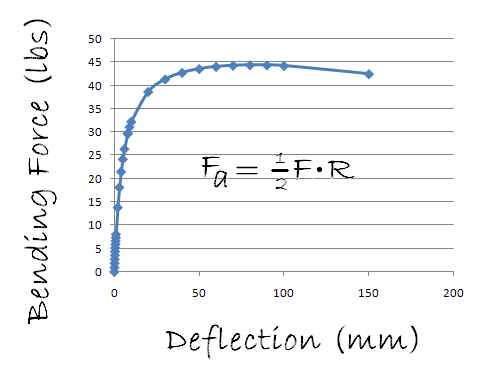

(By the way, this arrow will have a FOC of 17% - see Front Of centre for the significance of this.) The starting point for our discussion on how far it will bend is to use the critical load under which it will buckle. This is the critical load we mentioned above. The effect of the string on the arrow is to bend it. More power will bend it more, but not faster. The amplitude of the vibration is determined by the force you apply to the arrow (in fact by the force of the arrow on itself because of being accelerated, but that is getting too technical), its length, weight and stiffness. The frequency of the vibration is not. The critical force that buckles the arrow is defined by Euhler as: |

|

|

Reports were received of a CLP over 200% that is still accurate. When thinking this over, you may realize that the weight of a shaft relates only to the spine, if the shaft was built as light as possible - think material limitations. Above the minimum weight, it is independent of the static spine. But increasing the shaft weight does increase the dynamic spine. This is because the arrow accelerates slower if it's heavier, for the same draw weight. Remember, the arrow actually bends because it is compressed between the string, and the g-forces of the broadhead and shaft.Since the g-forces are less if it accelerates slower, this compression force is less. Also, this compression force is translated into the lateral force that bends the shaft, and since the shaft is heavier, the same force would have bend it less - more mass to move. At the same time we just said the force is actually less. Therefore, the displacement of the shaft is less. The heavier arrow, with the same static spine, actually has a stiffer dynamic spine. This in effect decreases the attack angle of the broadhead, and so increases accuracy. |

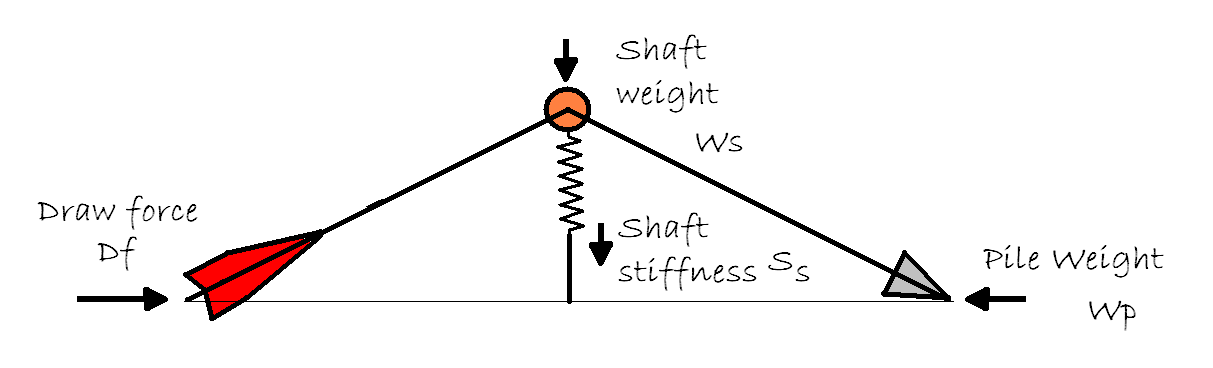

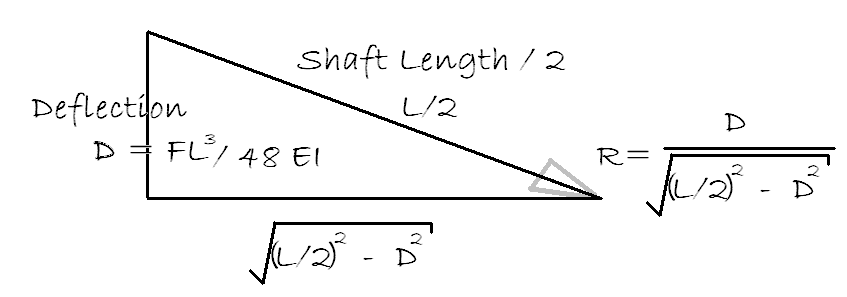

Important to notice is that the arrow bends not according to the bow’s draw weight, but according to the "g-forces" it experiences being accelerated. This force is twice the product of the arrow’s pile weight and acceleration. Also notice that weight behind any point on the arrow’s shaft, cannot add to the weight that bends the part behind it, but instead adds to the weight that resists the bend. Therefore the total weight that bends the arrow is the pile weight plus about half of the shaft weight (Wp + Ws/2). Also the fraction (R) of the force that bends the arrow is proportional to the ratio of the already existing deflection, to half the distance from the nock to the point: |

The spine, modeled as a spring, resists this bending force, and this resistance increases with the deflection. If the shaft is perfectly straight then the curve of the axial force needed to bend the arrow starts of at its critical buckling force, and decreases as you bend the arrow. To see if this makes sense, we can draw a curve of the deflection and compare it to the axial force needed to bend the arrow. More realistic, if the arrow is not perfectly straight, or the force is slightly off centre, the axial force curve looks like the one shown here. Calculating the critical buckling force the arrow, in this case, 47.2 lbs (calculated by the approximation done by Euhler's equation), we can see that it closely resembles the curve’s maximum of about 45lbs. |

Another interesting feature of this model is the decrease of the resistance against deflection as the arrow is bent beyond a certain point. This resembles the catastrophic failure of an arrow that is pushed too hard - it reaches a point where the arrow needs less force to bend it further than it is currently supporting, and collapses. |

You will recall I mentioned earlier that any mass in front of a certain point on the shaft bends it, and the mass behind this spot resist the bend. If you add all the weights before and after all points on the shaft, you will see that the shaft weight adding to the bending force is half of the shaft weight, and the part that resists it is the other half of the shaft weight.If we take these forces and apply them for a fraction of a millisecond to the model each time, until the arrow escapes the string, we can calculate how far it bends. |

| Parameter changed | Range | Deflection (mm) |

| Draw weight | 50 to 90 lbs | 4.6 to 12.8 |

| Broadhead weight | 65gr to 200gr | 7.1 to 10.6 |

| Spine | 200 to 600 | 3.8 to 15.3 |

| Shaft Weight (gpi) | 6 to 14gpi | 10.4 to 7 |

| Shaft length | 26" to 32" | 5.2 to 9.7 |

| Arrow Straightness | 0.006 to 0.001 | 8.4 to 8.0 |

| Arrow Rest | 0 to 2 mm out of place | 7.2 to 11.8 |

| Nock travel | 1 to 4 mm deviation | 3.8 to 10.7 |

There are many and varied factors influencing dynamic spine. The model presented here, based on a simple interpretation of Newton’s laws of motion and numerical analysis, predicts the effect of most of these parameters. The prediction of the bending of the shaft during release may not be extremely accurate, however the changes in the bending is fairly consistent with what would be expected from a real arrow. |

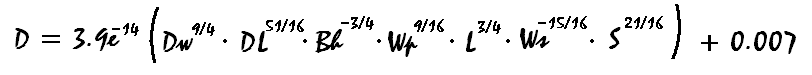

(Dw draw weight, DL draw length, Bh brace height, Wp pile weight, L shaft length, Ws shaft weight, S spine) |

For example, for a pile weight 215gr, gpi 13, spine 280, 30" draw length, 7.25 brace height, 72 lbs and 29" shafts, it predicts a deflection of 8.5 mm. I have a suspicion that this is a fair deflection for a 600gr arrow at 262fps. Easton’s spine charts in general try to keep the deflection of the arrow below 10mm. I would suggest you can start at 10mm, and decrease the s-spine of the shafts you test, to about 5mm. The best value will very much depend on your bow, since nock travel, inherent from the bow’s design, will place a limit on the stiffest arrow that still group nicely. |

Now let's look at traditional bows and dynamic spine... |

The total weight of the arrows he tested varied from 291 to 500 grains, the s-spine from 700 to 390, the length from 32.3 to 27.4", and pile weights from 89 to 180gr. The largest error was on the arrow with the smallest shaft weight (5.9gpi), and it was a mere 3.1 Hz more than the measured value of 87.6Hz. The equation describes 98.7% of the measured values - as theories go, this is GOOD. |

Arrow Wt L Wp Ws S Fm Fp Error Wood HPD 500 32.3 126 10.9 550 50.4 49.6 -0.8 X7 1914 375 28.8 100 8.9 660 65.9 64.1 -1.8 XX75 2213 440 30.6 129 9.5 460 67 65.2 -1.8 X72314 525 30 180 10.8 390 68.9 69.3 0.4 Cartel Tri 700 291 29 92 6.1 700 75.8 74 -1.8 ACE 520 292 30.3 89 6.0 520 79.7 78.8 -0.9 ACC 560 325 27.4 103 7.3 560 83.5 85.5 2.0 ACE 520 308 28.5 120 5.9 520 87.6 90.7 3.1 |

The next question you will ask now is what frequency is the correct frequency for your bow. Stu Miller has developed and excellent spine calculator for non-compound bows. It has a collection of a huge number of commercial shafts, and he actively keeps this up. You will find it easily with Google. I used this calculator of his to compare results of my model with his empiric formula (empiric: based on describing the relationship and not explaining it). (Just a short reminder: The frequency will determine how fast the arrow vibrates or bend, and therefore how much time it will take to move the fletches out of the way of the riser as it passes to the side of it.) |

D is draw length, B brace height, F draw weight, and Wt is the total arrow weight. |

Wp Ws S DL Bh DF L Wt fps millis Fn(arrow) Fn(bow) Error(Hz)

xx75 2213 150 9.5 460 30 8 50 31.5 449 194 19.8 54.2 50.6 3.7

125 9.5 460 30 8 60 30.65 416 219 17.5 57.7 57.1 0.5

100 9.5 460 30 8 70 30.13 386 244 15.7 60.3 63.6 -3.3

1914 150 8.9 660 27 8 46 29.3 411 179 18.6 54.1 53.8 0.3

150 8.6 660 27 8 56 27.8 389 202 16.5 61.1 60.6 0.5

125 8.6 660 27 8 65 27.4 361 224 14.9 63.3 67.3 -4.0

|

These arrows are matched to the bows using Stu Miller’s calculator. As you can see the frequencies we predict is slightly different. In the next table, I have matched the arrows to the bows using the frequency. You may notice that according to this prediction, the last arrow may be slightly too short. |

Wp Ws S DL Bh DF L Wt fps millis Fn

xx75 2213 150 9.5 460 30 8 50 32.8 462 192 20.0 50.0

125 9.5 460 30 8 60 30.8 418 219 17.5 57.1

100 9.5 460 30 8 70 29.2 377 246 15.6 64.2

1914 150 8.9 660 27 8 46 29.4 412 179 18.6 53.7

150 8.6 660 27 8 56 27.91 390 202 16.5 60.6

125 8.6 660 27 8 65 26.46 353 226 14.7 67.9

|

|

| Further Reading: JP de Villiers, AB&A, Oct 2008, p52, "FAQ" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Dec 2007, p30, "Arrow Spine" Harry Marx, AB&A, Mar 2009, p30, "Dynamic Spine and Building Heavy Arrows" Harry Marx, AB&A, in press, , "Dynamic Spine II" |

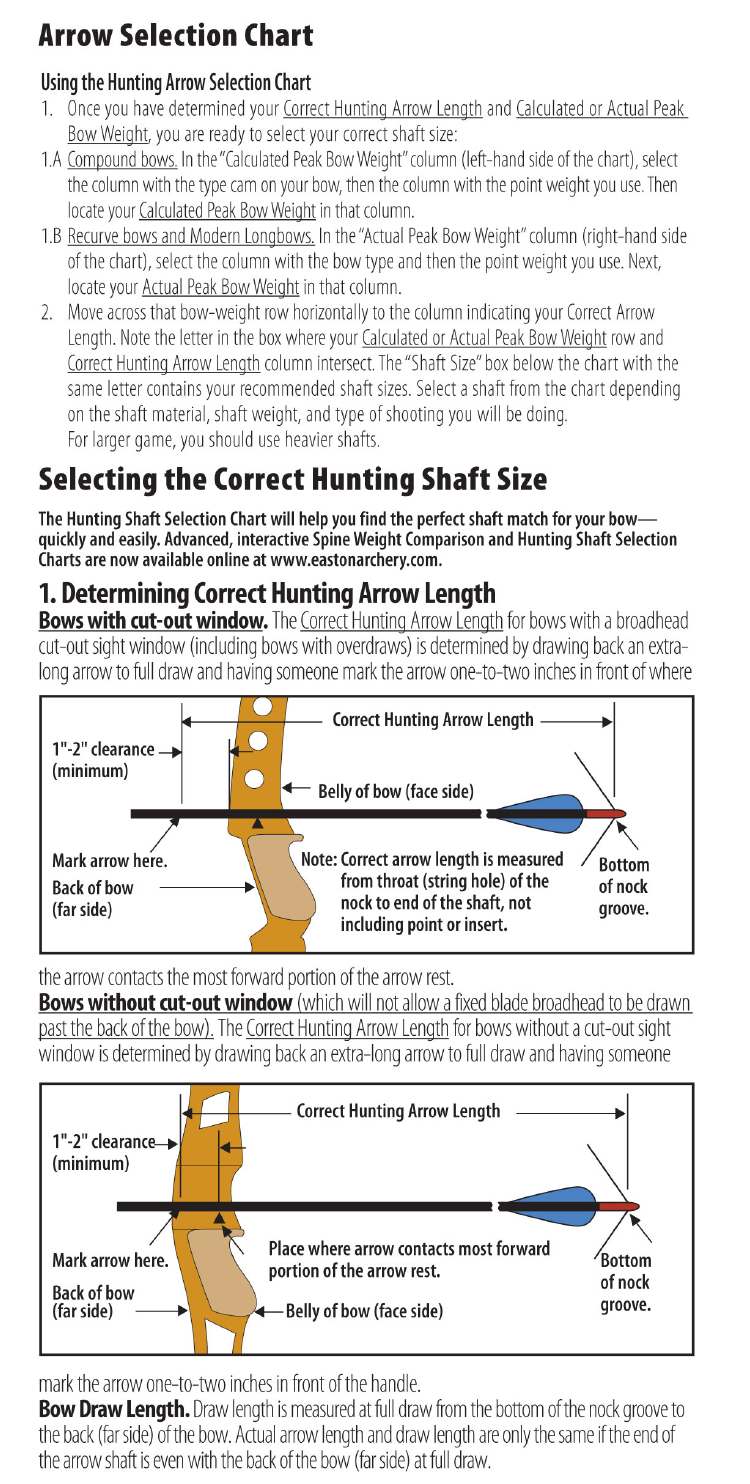

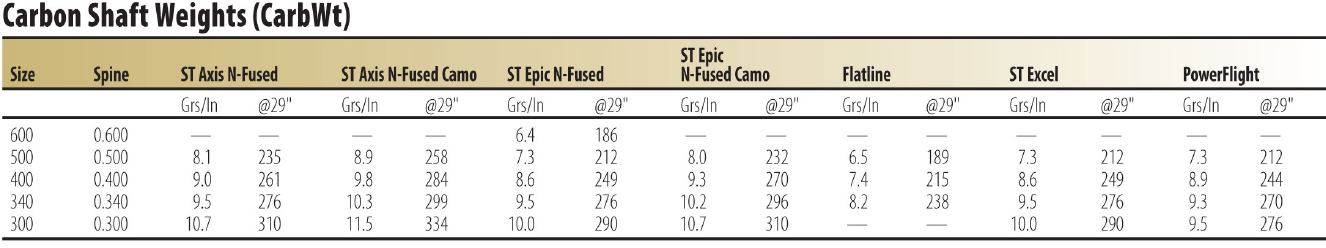

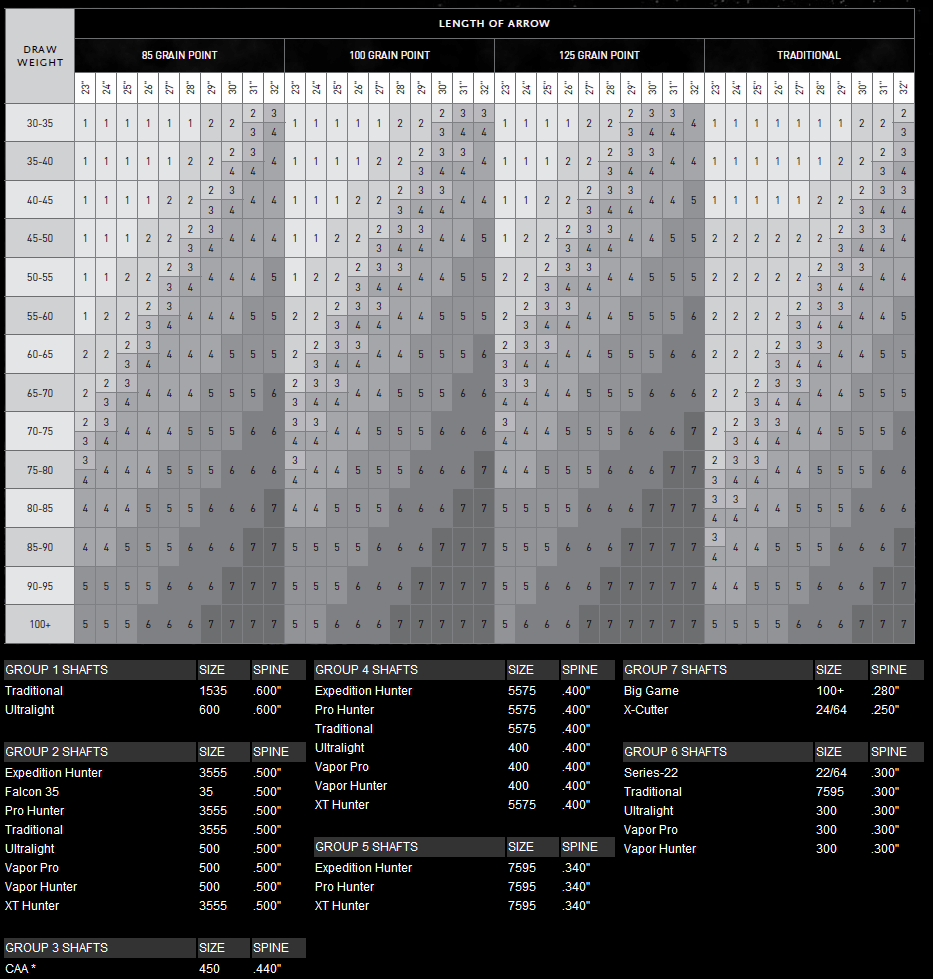

3.5.8.1.1 Easton Arrow selection charts

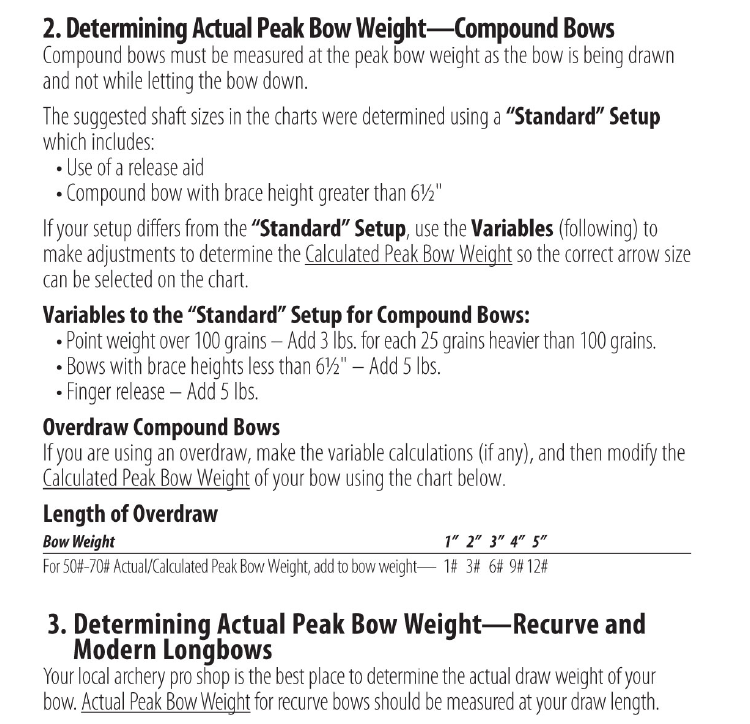

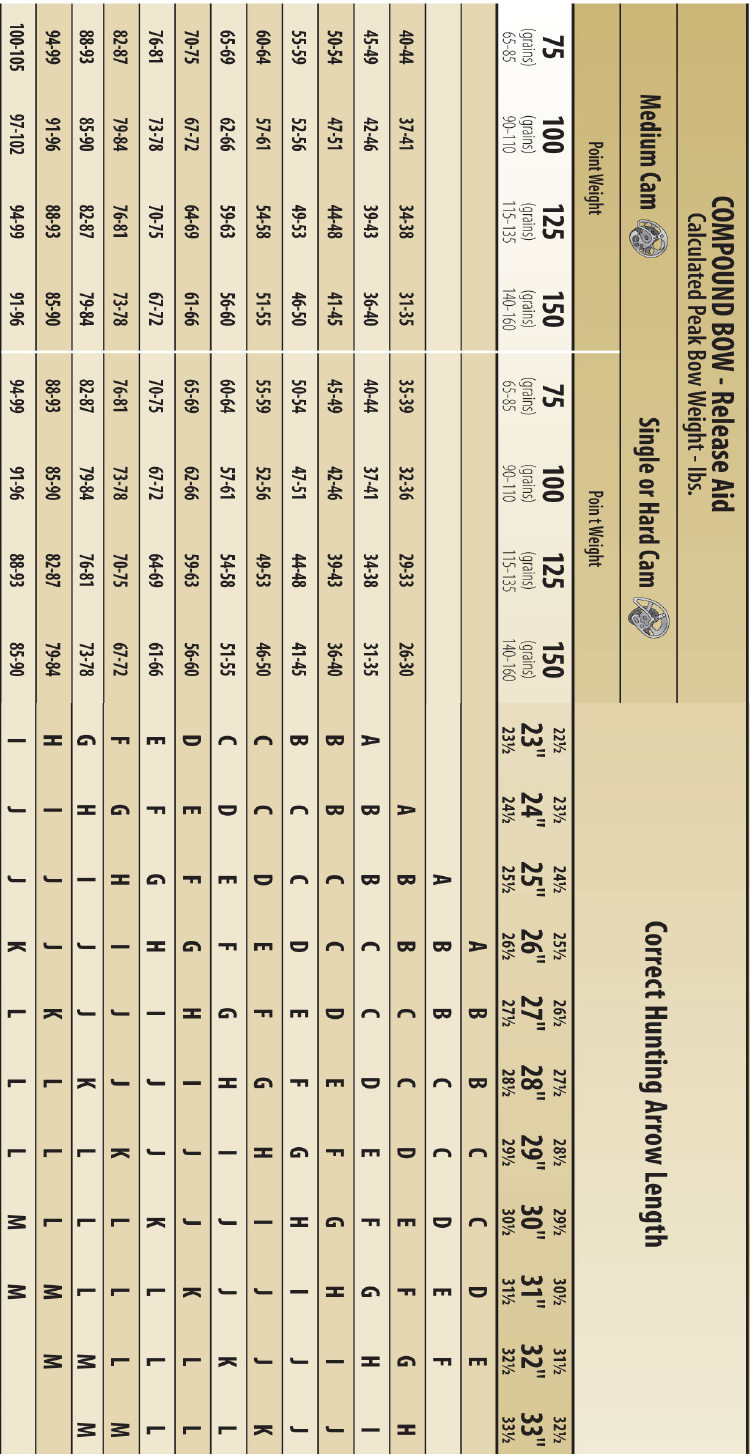

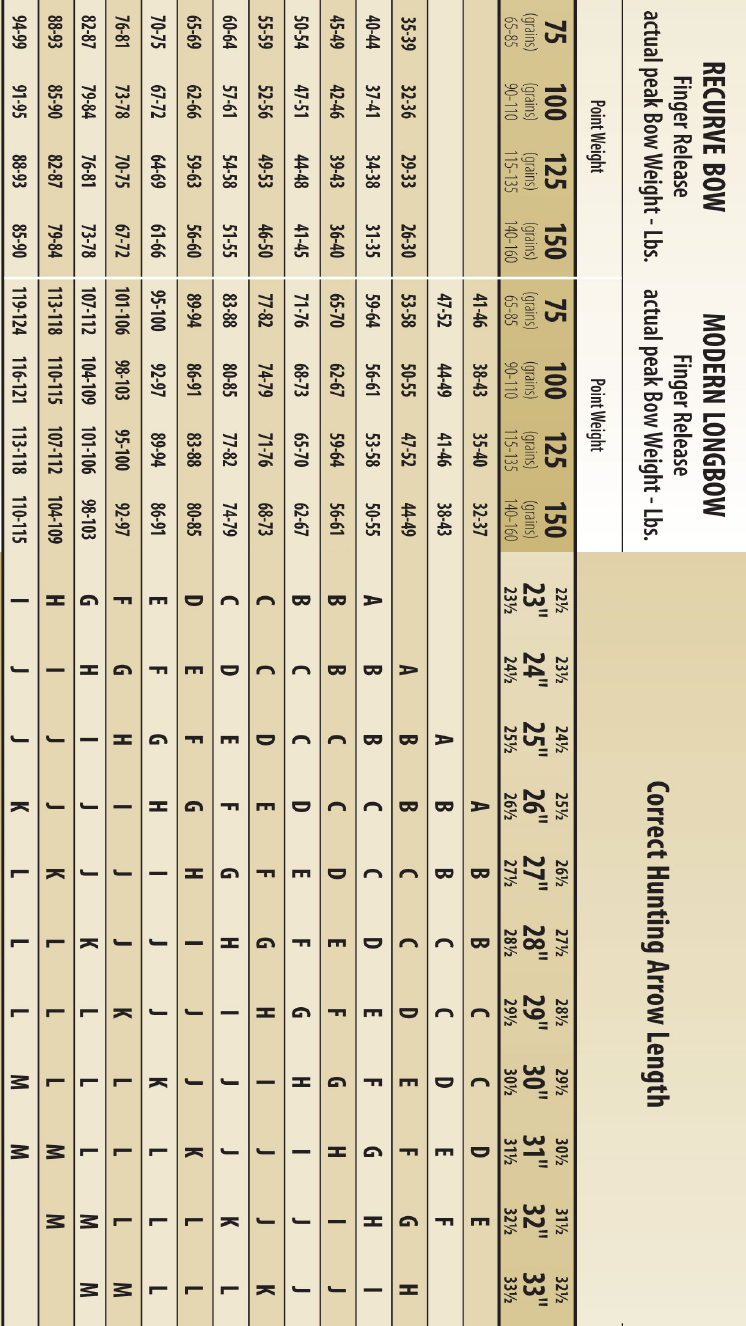

These are the charts for Easton and GoldTip. We include it here for instructional purposes. Although the specific arrow models change, the s-spine requirements is always relevant. |

3.5.8.2 Arrow Spin

|

Once the arrow’s spin reaches the rotational speed at which it can’t be spun quicker, due to the angle of the fletching, this drag falls away, and the arrow no longer loses speed to spin it. If the arrow now looses speed due to gravity or friction, it can actually be spinning faster than its fletching angle and speed dictates. This can decrease the stability of the arrow at long distances(>60Y), as it moves the centre of pressure forwards. Quantifying this effect has been attempted, but for now you should just take note of this effect. |

|

Increasing the size or angle of the fletching usually only works to a certain degree. Then the increased rotation speed actually causes this unbalanced arrow to start to wobble. It is therefore not wise to try and stabilize an already wobbling arrow with bigger fletches. The better solution is to balance the arrow, or to get rid of it. If the unbalance is due to the broadhead, you can try another broadhead on it. Sometimes it’s due to the "insert" not being inserted straight. Mostly it’s due to a used broadhead that bent slightly during a previous shot. Spinning the arrow on its tip or in an arrow spinner usually detects such an unbalance. Sometimes you only see it as a unwillingness to group. |

|

The spine of an arrow must match the bow to start of with. In hunting, the spine must also match the resistance especially in heavy bows with fast arrows. Most spine charts give the spine stiffness for acceleration. This is fine for target shooting but not for hunting. In hunting, the arrow sometimes come to a stop in a shorter distance than it accelerate out of the bow, [for eg. when] striking a bone. |

|

The less an arrow flex, the more momentum it has. The faster it stabilizes the better it flies." |

| Further Reading: John Dudley, AB&A, Mar 2008, p30, "The Best Fletching For your Arrows" JP de Villiers, AB&A, Mar 2008, p48, "FAQs" Sampie Stoffberg, AB&A, Jan 2009, p56, "Die keuse van vere" |

4 In Practice

|

4.1 Using a bow

| Further Reading: Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Jan 2007, p42, "Boogterme" Rean Steenkamp, AB&A, Apr 2007, p47, "Eye Dominance" |

4.1.1 Tuning a bow

A bow and arrow is a complicated machine that needs expert tuning for optimal hunting performance. We recommend that a bow hunter should practice to shoot accurately with the highest poundage possible. It is recommended that the bow is tuned in order to maximize the energy transferred from the bow to the arrow. Thus the right selection of combined optimal equipment is critical and each component of the bow hunting set-up must be carefully selected. |

4.1.2 Cam Tuning

Although cam tuning is (almost) always done in the shop, you need a bow press and a bow shooting machine, we discuss it here for the importance of this step. And contrary to popular hype, even binary cams needs to be tuned. Of course this does not apply to single cams... |

4.1.3 Paper Tuning

The purpose of paper tuning is to set the arrow rest's height and the preliminary lateral position. You need to do paper tuning, and then "walk back tuning", to get good flight from arrows with hunting points. |

| Further Reading: JP de Villiers, AB&A, Nov 2008, p52, "FAQ" Herman Brand, AB&A, Sep 2007, p13, "Paper tuning your bow" |

The rest should be adjusted up or down, until the shaft's tear is horizontal. |

4.1.4 Walk back tuning

This is done with hunting points. The sight is first tuned for 20, 30, 40 and 50Y. Once you are no longer able to increase the precision with the lateral adjustments of the sight, you can start with walk-back-tuning. |

Then you can tighten the rest's screws and check it once every 1000 or so shots. |

| Further Reading: JP de Villiers, AB&A, Sep 2008, p52, "FAQ" John Dudley, AB&A, Nov 2007, p30, "Walk-back tuning with broadheads" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Nov 2007, p55, "Stel jagpunte in - maklik" |

4.1.5 Nocking Height Tuning

What is the influence of the nocking position on how a bow performs?

|

The horizontal axis of this graph is inches drawn, while the vertical axis is millimetres above the centre line. Since the arrow rest is at 0" drawn, you can extent the general direction of the nock with a pencil, and see where it will cross the 0" point. For the bottom line (1mm low) it will fly over the shelf at about 14mm, whereas at 1mm higher, its being pushed on a line below the shelf!

|

But I think we are not really seeing the drastic effect these nock movements have yet. |

Since the D-loop is usually done over serving, the serving can act as a thread on which you "screw" the D-loop up or down. This also makes for "fine tuning", since the serving thread is typically less than 0.5mm. So you have a fairly fine thread on which to rotate the D-loop.

|

|

4.1.6 Tuning arrows

The last step tuning your setup is looking at the arrows. By this time arrows with broadheads and fieldpoints should be hitting close to each other. If they do not, it most probably means that the arrows bend too much as they leave the bow, i.e. they are under-spined. You can try more stiffer shafts. |

4.1.7 Practicing

Confidence in your ability to hunt is locked up in the aged old saying "practice makes perfect". SABA simulates hunting conditions on a monthly bases on African animals in 3D competitions in order to harness our members with knowledge and confidence of optimally used equipment and arrow trajectory in real hunting light conditions. "Bokkoors" can’t be simulated but can be overcome with the confidence coming from experience in the hunters shooting ability. Every aspect of the hunt should be coupled with confidence. |

4.1.8 Anchor Points

Archery is almost always a mixture of old and new, and anchor points are a point in proof. Shooting consistently is only possible if you have a constant anchor point, and bow grip. In time, with new developments that aid with consistency, many archers neglect the anchor point and grip. The rationale is of course that with a peep, who needs an anchor point? In fact, as of date there are even two products on the market that "eliminates" a peep, and therefore can be seen as to make a consistent anchor point even less important. |

|

Some archers anchor below the chin, some against a lucky tooth, some behind the yaw bone, and so on. I anchor with a knuckle into the back of my ear. Of course, when using a mechanical release, your options are very much defined by the type of release. One interesting variation is to anchor the thumb behind the neck. This provides a very stable support for a very long draw length. Some archers also believe in a third anchor point. This is usually done by touching the tip of the nose to the string. Kisser buttons are also popular with traditional archers, which is a brass nut or even just a small leather strip knotted to the string. The idea is that you put this physical marker on your mouth or lips, on a particular spot each time. |

On holding the string with your fingers, there are two schools: the Mediterranean way, and the apache way. The Mediterranean way uses two fingers above and below the arrow, while the apache hold puts just one finger above the arrow. Some people shoot with three fingers below the arrow, and none above. |

As you can see on this drawing, the string arm is also supplying lift to the bow-arm when it draws the bow. The height of the anchor point above the shoulders determine how much of this pull is used to keep the bow up, vs. drawing the string back. |

If you experience this again, try pulling harder at the string, and you will see the bow lifts suddenly. This "below the spot freezing" is not a sign of panic, it is more an indication that you are relaxing your body, as it should be. |

4.1.9 Draw length

Determining the correct draw length is important, and very easy. Measure your arm's span from fingertips to finger tips, stretched out to the sides against a wall, and divide this with 2.5. Use this to set the bow's draw length, and then you can fine tune it further with either adjusting the cams, or string length, or even the D-loop length. |

4.1.10 The Grip

The solution is of course that when you do relax your chest muscles, you must pull a bit harder with your back muscles, to get the string-arm's shoulder to rotate further back, and therefore to pull slightly harder - to lift the bow into line again. But after all, the anchor point you use, should be comfortable, and by definition, this will be close to the point of balance. When talking about bow grips, I got the following advice. The top of the handle should lie in the V of the thumb and the hand, and the bottom part should rest against the heel of the hand, between the thumb and the hand muscles. In other words, the top of your hand should be about 40 to 45 degrees turned out, while the bow is vertical. |

|

There are a few products on the market that promises to eliminate bow torque. |

|

4.1.11 Aiming Technique

There is generally two ways to aim, without or with a sight. When shooting without a sight, you have to judge the trajectory of the arrow. This takes extreme levels of practice to achieve. Mostly used by "traditional hunters", which are shooting with longbows and recurves. There are a few archers who have achieved unbelievable accuracy in this way, however, most hunters are more successful using sights. Shooting instinctively does have the advantage of being fast. It is possible to aim and shoot in much less time than it would take using sights. This is a technique to be practiced, and very little else can be said about it. |

|

In exactly the same way that a thin myelin sheet increases reaction time, overriding these reflexes with conscious control, takes way longer. This of course increases the unwanted shaking movement. With practice, an action becomes unconscious. This is indeed what happens, and in becoming unconscious, it also becomes faster. Further practice, and honing of this unconscious skill, will reduce the time for feedback even further. The conclusion to cure the wandering sight syndrome is to relax and not to think about it. Aim like riding a bicycle. |

|

Generally however, you will find that you approach the target with the open area of the sight. If the pins are fastened onto the right half of the sight ring, the left side will be open, and you will find yourself approaching the target with the pins generally from right to left. This would suggest the best pin configuration to be hanging from the top of the ring, which sadly is not available. In fact, single pin sights usually have the pin fixed to the bottom of the ring. |

4.1.12 The Release

One of the most important steps in shooting is of course the release. Target archers have a great advantage over hunters, in that they can employ what's called a "surprise release". In effect, the release is done in such a way that the archer is unable to predict the exact moment the release will occur. This in turn implies that they are not able to "compensate", or pre-empt it, with some muscle action. The idea not that the release should take you by surprise, it merely means that you should not be able to pre-empt the exact moment it will occur. |

|

|

A reminder - the palm of the hand holding the bow should be about 45 degrees with the bow. Also your elbow must be bent - if not, the bow's draw length is too long. Your elbow should also be bent away from the bow, and not down (else you will get string slapped). Now the follow through - your hand should just keep on pushing the bow straight forward as the follow through. If your arm was straight, the bow will instead jump to the left. With the bent arm, it travels forward and do not affect the arrow's flight... |

| Further Reading: Roy Gaylard, AB&A, Apr 2006, p36, "Instructions for beginners" |

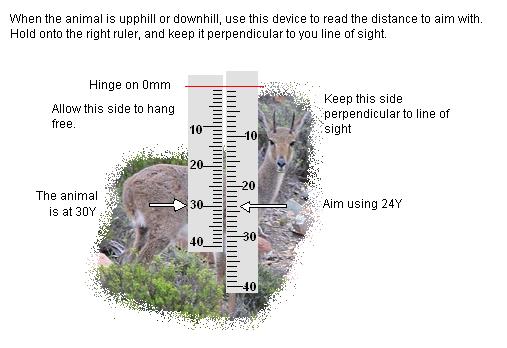

4.1.13 Shooting uphill or downhill

The trajectory of an arrow is actually quite a complex model. The complicating factor is that friction in air is dependent on the square of the velocity of the arrow. It is of course also dependent on the arrow design, its broadhead and fletches, and how it travels. An additional factor is the angle of the fletches. This causes more friction during release, but potentially a straighter flight, endless friction at the last stages of the flight. |

Newtonian Model

Angle

45: 6.5 14.2 21.5 29.1 36.7 44.4

40: 7.5 15.3 23.3 31.4 39.7 47.8

35: 7.7 16.5 25 33.5 42.2 51

30: 8.7 17.2 26.4 35.1 44.2 53.4

22: 9.2 18.6 28 37.6 47.2 56.7 The Cos-Rule:

15: 9.4 19.4 29.1 39 48.7 58.7 which is the same up or down

10Y 20Y 30Y 40Y 50Y 60Y 10Y 20Y 30Y 40Y 50Y 60Y

-15: 9.9 19.4 28.9 38.3 48 57.4 15 10 19 29 39 48 58

-22: 9.4 18.6 27.8 36.7 46 55 22 9 19 28 37 46 56

-30: 8.9 17.5 25.9 34.4 42.9 51.2 30 9 17 26 35 43 52

-35: 8.4 16.5 24.5 32.4 40.6 48.5 35 8 16 25 33 41 49

-40: 8 15.3 22.9 30.3 37.9 45.3 40 8 15 23 31 38 46

-45: 7.5 14.2 21.2 28 34.9 41.7 45 7 14 21 28 35 42

|

An exact formula for calculating the compensation for uphill and downhill shots does not exist. However, the following approximation also works well: |

|

Some rangefinders already calculate this for you. With older ones, you can pick some other object that is directly below or above the animal. What is also important about these shots is the way in which it's done. You should preserve your shooting form when doing so, and not lower or raise your bow arm to make them, but bend at the waist. Draw and anchor the shot as if the target is straight ahead. Then bend in the waist to aim. |

| Further Reading: Harry Marx, AB&A, Mar 2008, p14, "Compensating for shooting at a slope" |

4.1.14 Shooting through a gap

Often when you walk and stalk, and even more often if you shoot from cover, you have only a narrow gap to shoot through. This gap may be directly in front of you, but it may be anywhere between the animal and you. Knowing the arrow's trajectory can allow you to miss these obstructions, and shoot a perfect shot. |

|

The arrow passes through the loops at various distances. What is very useful to note is that if you moved loop E, such that the arrow falls through it on the 30Y pin's line of sight, that loop will be at 30Y. In other words, if the loop (or gap) is at 20Y (as is loop D), the arrow will fall through it if the 20Y pin's line of sight is on it! |

4.1.15 Target Panic

Every archer and hunter experiences target panic at least once. It can take a number of different forms: the inability to release the arrow (freezing), the inability to move the sight on to the target, or snap shooting - releasing the arrow the instance the sight passes the target. |

|

Shooting at 5Y with your eyes closed is also suggested frequently. I found this generally to increase anxiety, and do not suggest it. You will probably need to return to these treatments in time. I found it useful to include these activities as part of my normal exercise routine. |

If you have been shooting for a long time, a different problems starts to rear its head. You start to shoot more "instinctively" (without thinking). This sometimes causes you to "lose control" of your trigger finger.As the pin approaches the target, the shot simply goes off - and you never instructed your finger to pull. You can easily measure the degree to which you are already suffering from this. When aiming next time, put the pin on the target, touch the trigger, but do not pull it. If you can do this, you are still "in control". If you cannot, well, you have a problem. The feeling is similar to the urge you get to close your eyes when someone threw sand in them. It is almost unstoppable - the shot MUST be done... I know, since I suffer from this. But luckily there is a good treatment for this as well. You see if some action is being performed unconsciously due to repetition, you only need to change the action and it will "bounce" back into consciousness, or conscious control. The treatment in this case is to change the finger you pull the trigger with. Doing this change often keeps the process from falling into unconsciousness.

|

| Further Reading: John Dudley, AB&A, Jan 2008, p15, "Curing Buck Fever and Target Panic" |

4.1.16 Arrow Care

Make sure you arrows are clean. When shooting into 3D targets, often some of the material sticks to the arrow. This should be removed before you can shoot with the arrow again. This material not only make the arrow lie incorrectly on the rest, but can also bump it in any direction as it is released. You can rub the shafts in hard, old soap to protect them against it. |

4.2 Preparing for the hunt (overview)

Your equipment must be in top working order and you must know which animal category can be hunted with the bow equipment as a whole. Prepare thoroughly and check each component for optimal mechanical operation. When arriving at the game farm, be thoroughly briefed and get the farm’s rules and regulations together with a price list of animals that may or may not be hunted. Always have a knife and a good wire cutter in your daypack to remove snares set by poachers. |

4.2.1 "Walk and Stalk"

JC Botha, former chairman of SABA, has the following to say about walk and stalk":

|

A pair of protective gloves is essential for when you need to walk on your hands and knees. I use second-hand military police leather gloves and cut them down to size. They are very strong and last for many seasons.

|

Also when spooked they prever to move against it. This is all because the smell and sounds are carried by the wind, and allow the animals to "see throught" the bush. Moderate wind will also provide you with a sound cloak - in that the grass and leaves' sounds will drown your movement's sound.

|

4.2.2 Hunting from hides

Whenever a rifle hunter pictures this scenario, a bowhunter in a hide, waiting for animals to come drinking, salt licking, or feeding from lucern or other special feeds, they get REALLY agitated. Aparantly this is the worst form of un-ethincal hunting... But before we discuss this issue, also discussed later when we talk about ethics, let us first discuss how to hunt from a hide.

|

Now, back to the ethical thing. One way to measure the level of "fair chase" in a hunting technique, is to count the number of animals taken with this technique, per hour spent doing it. From my personal experience I have been more succesfull (animals shot per hour) with rifle on foot, LESS with bow in hide, and least with bow on foot. So although there isn't a "chaise" involved, there is a "wait" involved... The right animal must approach the hide close enough, it must stand still, and in a huntable posture, with no obstructions.

|

| Further Reading: Herman Brand, AB&A, Apr 2007, p31, "Jag uit 'n Skuiling" Pieter Oberholzer, AB&A, Sep 2007, p49, "Die Onderskatter Boonstoel" |

4.3 Hunting Fish

| Further Reading: Herman Brand, AB%A, Oct 2006, p50, "Visskietseisoen is hier" Cleve Cheney, AB%A, Dec 2006, p8, "Bowhunting Fish" Herman Brand, AB&A, Dec 2006, p50, "Voorreg om vis te skiet" |

4.4 Hunting Birds

4.5 Snakes and Snakebite

The first rule about handling snakes is - keep out of there way. They are more afraid of you than you of them. And in general they will flee, or freeze. Only if you are really on them, stepping or otherwise, will they defend themselves in the only way you can, if you only have teeth... |

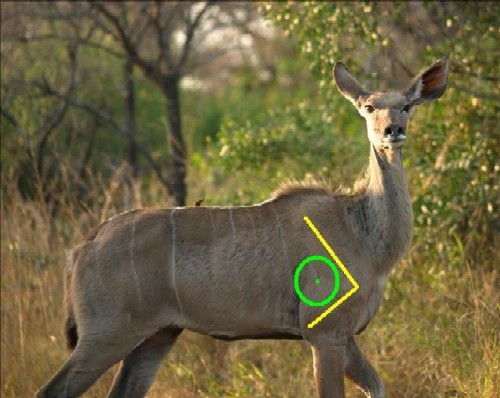

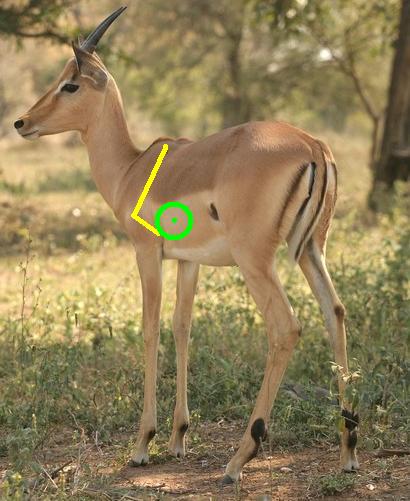

4.6 A Primer on Shot Placement

The animal always comes FIRST. A picture of you and a successfully bow hunted animal, capture what this book is all about. With the hunter in the background and the hunted quarry in front, the picture advocates to the world the essence of the skill of bow hunting in its truest form. The world looking at your picture sees the animal in the foreground FIRST and the hunter in the background.

|

|

|

|

In the above example, many hunters advocate to shoot for the furthest leg, which is still acceptable. It is slightly risky in that if you pull to the right, you may only hit one lung. |

|

|

|

The animal is also looking at you, already making it risky. And if the animals should jump at all at the bow sound, remember the small shot window, you missed it. Therefore it is not recommended at all. |

|

|

|

|

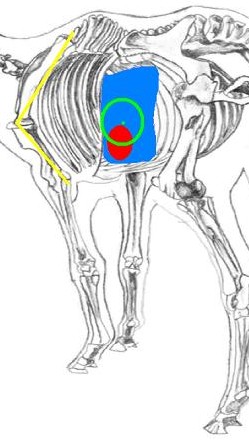

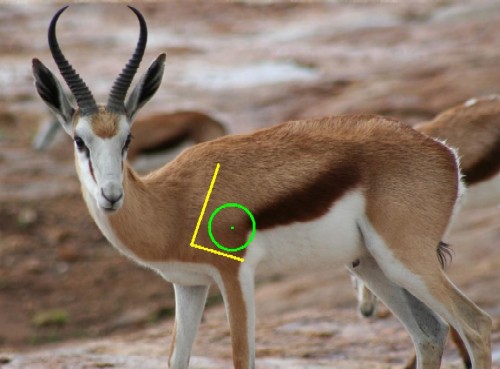

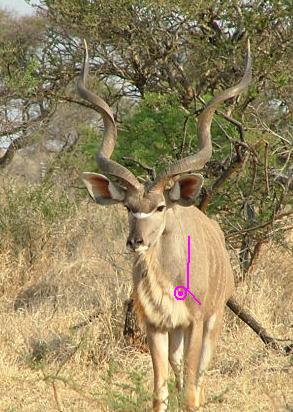

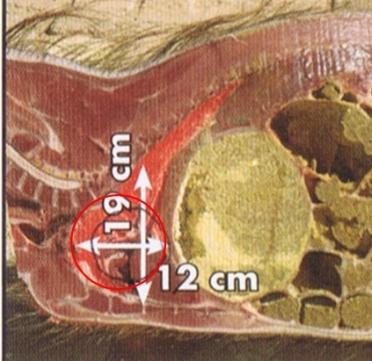

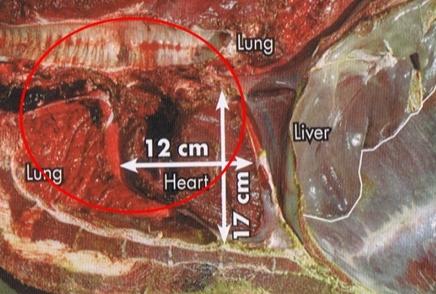

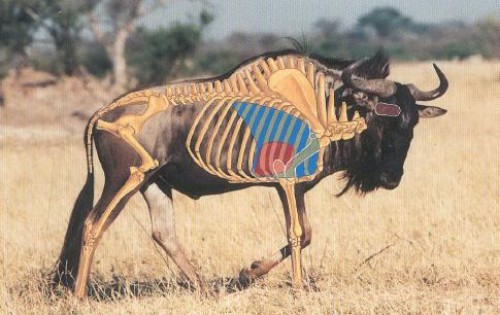

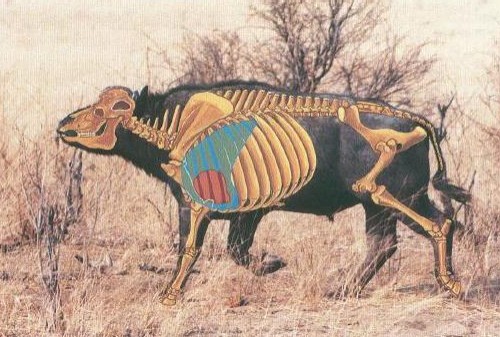

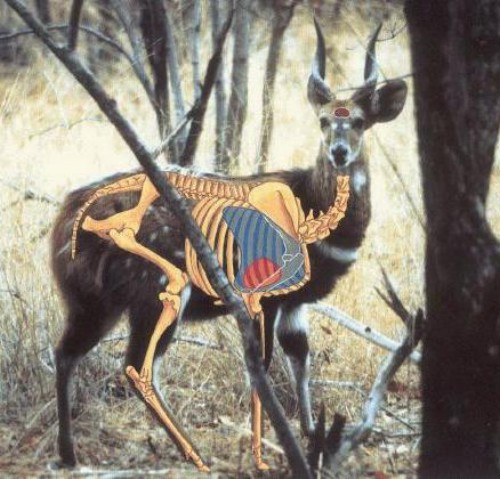

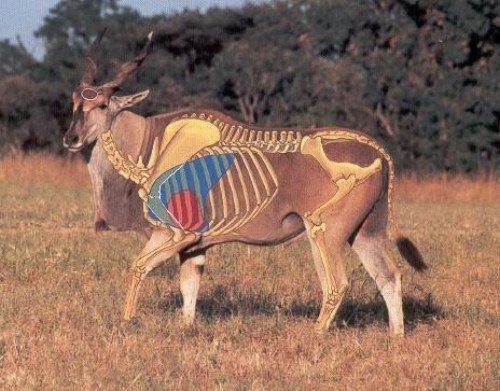

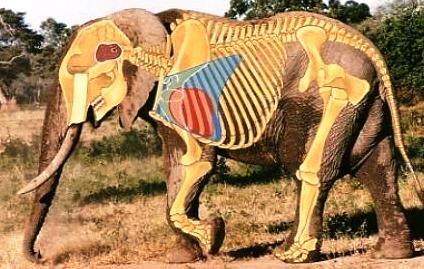

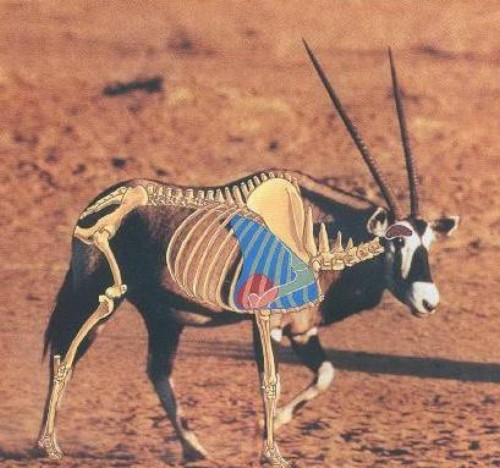

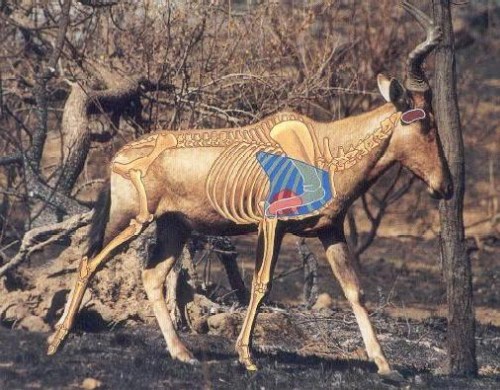

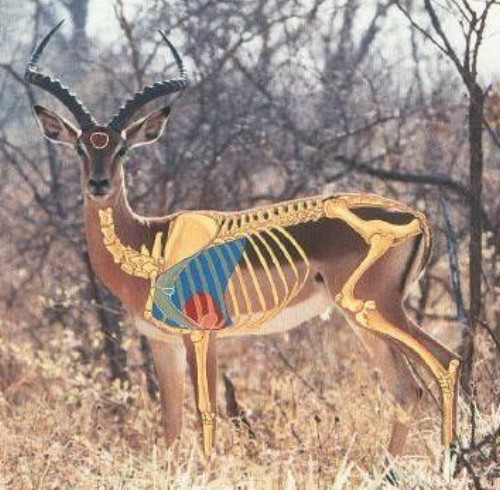

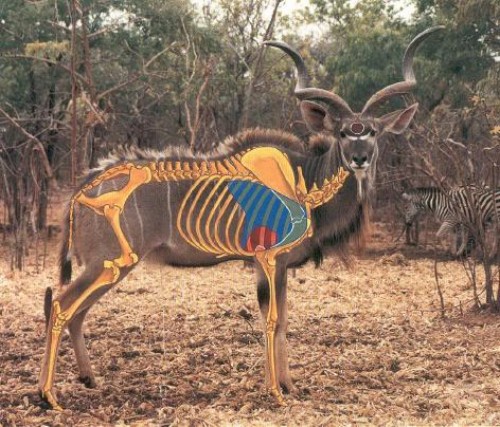

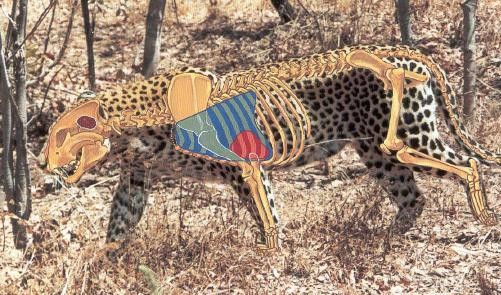

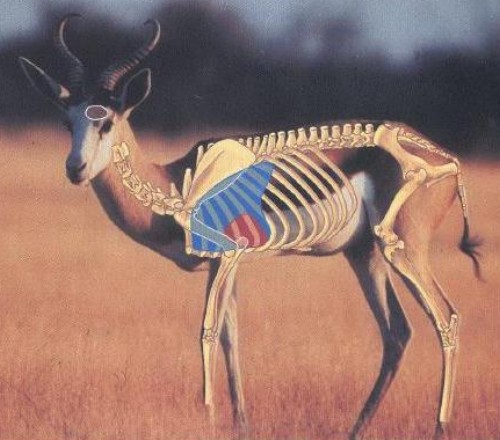

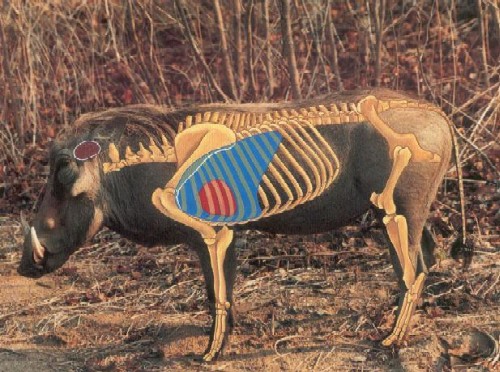

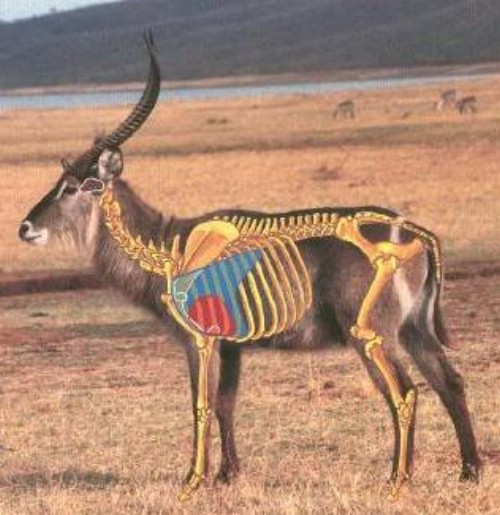

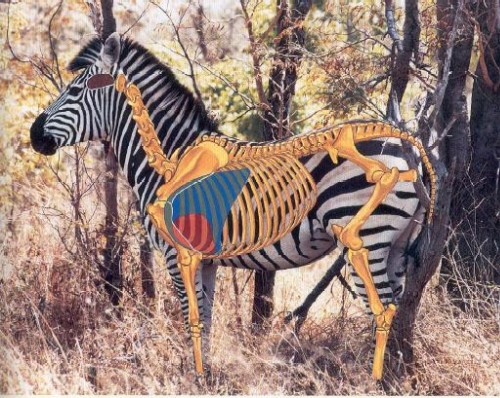

4.6.1 ...from the inside

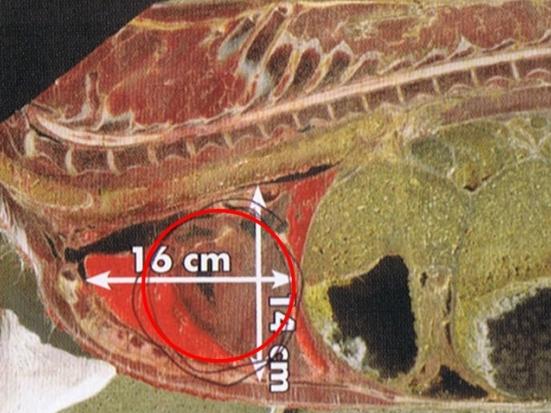

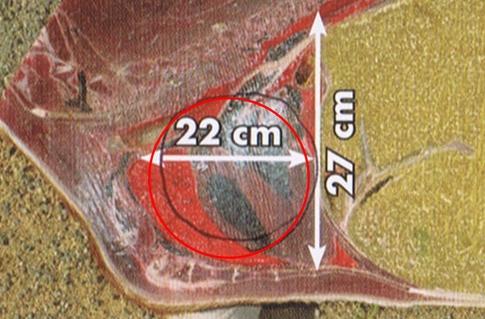

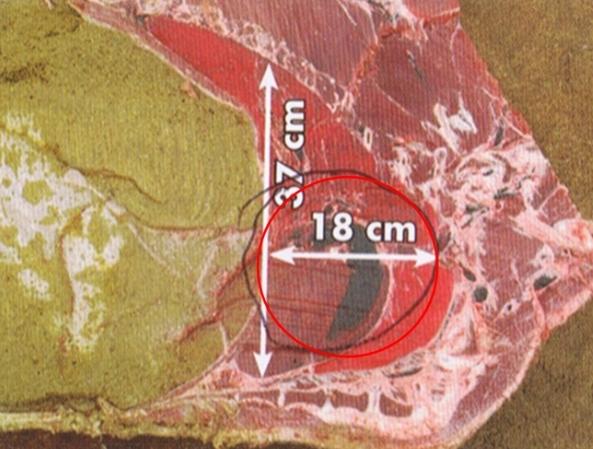

Here is an interesting perspective on vital area diameters. These animals were frozen and cut into half. This provides us with the position and size if vitals organs. Just as animals differ on the outside, the precise position and form of the internal organs also shows some variation. |

|

Warthogs are notorious for their toughness, and speed. |

|

Here we look at a Springbuck. Its vital area is about 5.5" at its narrowest. |

|

Blesbuck, with a vital area diameter of 8.5" |

|

Blue wildebeest, with a surprising 7". This is smaller than expected. |

|

And here we have a kudu, also about 7". |

Although these are interesting studies, one photo does not represent a specie. We do not know the age of these animals, nor does the exact cut through them looks like it cut throught the middle. |

| Further Reading: Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Mar 2008, p8, "In the Zone" Willie Oosthuizen, AB&A, Jul 2007, p17, "Shot placement for trophy purposes" David Guthrie, AB&A, Jan 2007, p10, "The G-Shot" |

4.6.2 Accuracy

The first thing about accuracy is arrow weight. You can ask the question, how close do my arrows need to be matched for weight, to shoot within 0.5 inches of each other? Here is a simple equation with which to calculate this:

dW = 2.(m+100).H.V2/(S2g). |

|

In general, when increasing the blade area, fletching area should also be increased. Some hunters suggest to use even 4x 5" fletches on 4 bladed broadhead. Of course, the better the bow is tuned, i.e. the straighter the arrow leaves the bow, and the quicker it stabilizes, the better the grouping you will get with broadheads. Lighter arrows also stabilize more quickly than heavier ones. |

|

If you find that the grouping does not change, but the broadhead shoots consistently off target,the problem can usually be corrected with bow tuning. |

| Further Reading: Sampie Stofberg, AB&A, Mar 2009, p42, "Wanneer om te skiet" Herman Brand, AB&A, Nov 2008, p57, "Stop en Verbeter" Sampie Stoffberg, AB&A, Nov 2008, p57, "Jaagskote in die Jagveld" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Mar 2008, p54, "Maklike oefen tegnieke om gou beter te skiet" John Dudley, AB&A, Jan 2008, p15, "Curing buck fever and target panic" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Oct 2006, p51, "Hoe kan ek beter skiet? (Part 1)" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Nov 2006, p50, "Hoe kan ek beter skiet? (Part 2)" Seppie Celliers, AB&A, Dec 2006, p49, "Hoe kan ek beter skiet? (Part 3)" Johan Smit, AB&A, May 2007, p30, "Oorkom plukskiet" John Dudley, AB&A, Sep 2007, p38, "Maximizing you hunting accuracy" John Dudley, AB&A, Oct 2007, p25, "Shooting Accurate Constantly" |

4.6.3 Estimating Ranges

Although it is highly recommended to use a rangefinder, the following techniques may come in handy if the battery goes down, or the device fails... Always bear in mind that you can for any technique simply divide the distance into two, and estimate the nearest half’s. Double it then for the whole distance. |

4.6.3.1 Ground Distance estimation

Learn to estimate a particular distance, say 10y, on the ground, towards the target. The technique is then simply to count how many times it fits into the total distance. You can also estimate multiples of 10 and then 20 yards, etc., and get the average. |

4.6.3.2 Angle Cards

These cards are marked with the apparent height of 1m at various distance intervals, when the card is viewed at a particular distance. |

4.6.3.3 Using your Thumb

This technique inverts the "angle cards" idea. Instead of comparing the apparent height with various pre-marked heights, we use the number of times a known/estimated distance at the target’s position, fits into a single pre-marked distance. |

4.6.3.4 Using a Ruler

Basically the same technique as the thumb idea above, but with the ruler you can impress more suckers, wink-wink. |

You could of course use anything with at least 10" marked on it (an arrow comes to mind). |

4.6.3.5 Measured apparent size at 10m or 10y

Another adaptation to the above technique is possible when shooting 2D targets, since they are printed on the same size paper! Walk up to 10yd away from the target, and hold up your bow at shooting length. The target will fill a certain width and height inside the sight, or on the riser. Make a mental note thereof. |

4.6.3.6 Known size / 100

There are two variations of this technique. They are very similar to the previous ones, but with slightly different accents, and can come in handy to cross check each other. These techniques also start with a known or estimated target size. But instead of using a fixed width a particular distance, use 1/100 of the target’s size. |

Disadvantages |

4.6.3.7 Parallax

This is an easy technique. Take a pencil, or even a sight’s pin, or field point. |

4.7 Camouflage

|

Any movement is very easily seen by all animals.When moving in the field, do it as slow as possible. When very close to your target, try to move only parts of your body at a time. It is of such importance that the lack of any movement becomes an ambush - which is so effective that some hunters feel it's not ethical! The best pattern that hides movement is no pattern at all. A single natural colour or a large low contrast pattern with blurred edges works better for a moving hunter. Smaller sharp edged, high contrast patterns work best for an ambush hunter. |

The silhouette defines your outline, or shape. Another aim of camouflage should be to break the hunter's shape. The use of high contrast on edges, as seen from a particular direction, is most effective. However, the moment you move, they become more visible. |

Never confuse camouflage for combat, with that for hunting. Although they can look similar, never judge them with a human eye. Check the patterns at 100 to 10Y. It should stay blotchy and fragmented, and never become a blob of a single colour. |

As a last word on camouflage, the best all purpose everywhere camouflage makes you look like something very well known, totally benign, and that's everywhere - a rock. If you walk through the field, how much attention do you apply to rocks? You are always looking at bushes, what's in them, behind them, and as for rocks, at most what's behind them. |

4.8 Waiting Times

|

|

4.9 Following a spoor

There are long and beautiful stories of trackers, and how with the faintest of evidences, they can tell you not only where the animal went, but the particular type, male/female, age, temperament, and of course, where they headed. If only we could write down the skill ... |

|

Blood when dried becomes brown. Small spots of blood dry within a minute of two in the hot sun. So you should be looking for brown and red. The blood normally is more smeared against the grasses and bushes as the animal walks, unless of course the bleeding is profuse. The blood gets caught up in the hair much like paint in a paint brush. |

Watery blood, with stomach contents is a bad sign - indicative of a gut shot. It IS going to be a long trek.If the whole arrow has blood on, it’s usually a sure sign of a pass through, and usually a good blood spoor. Antelope and dog blood clots on the ground generally within minutes, while pig blood clots in 3.5 minutes and equine blood (horses, zebras) in 11.5 minutes. |

|

|

| Further Reading: Cleve Cheney, AB, Nov/Dec 2000, p23, "Principles of Tracking - Part 2" Cleve Cheney, AB, Jan/Feb 2001, p17, "Principles of Tracking: Interpreting Sing - blood trailing - Part 3" Cleve Cheney, AB, Mar/Apr 2001, p18, "Principles of Tracking: Interpreting Sing - identification of tracks (mammals) - Part 4" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Mar 2008, p74, "A Tracking Notebook" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Feb 2008, p66, "Tracking by sound" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Jan 2008, p74, "Mud Tracking" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Nov 2007, p74, "Following a blood trail (Part1)" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Dec 2007, p74, "Following a blood trail (Part2)" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Oct 2007, p74, "Tracking: ageing sign - scats" |

4.10 Caping

4.11 Ethics

There are much written about ethics, and SABA will not say the last word on it. But we (SABA) want to start a process wherewith the bowhunting community can develop a mature and complete education on all aspects of bowhunting, ethics included. |

Therefore neither SABA nor probably anybody else can define "a fair chase". A really fair chase is probably only when you have to run down your quarry, and bite it to death. |

|

If we all can accept these points, we need not have any argument on ethics. Anything that is not solved by referring back to these principles, becomes opinions, and is subjective, and most probably will change in time and among cultures as well. Then a "fair chase" lies outside the scope of ethics, and becomes one of opinion.

Rean Steenkamp, editor of the African Bowhunter and Archer, has the following to say:

This illustrates the difference between ethics, opinion and a fair chase. The most important implication of these principles is that you have to shoot accurately, not with marginal or inferior equipment, and only if a safe and sure shot is available. This applies to ALL types of hunting. |

|

On these last rules: SABA supports the very old and universal rule, if you draw blood, you pay. There is no responsibility on the farmer’s side, or the PH, or the manager, to find the animal you shot. It was your decision to hunt there, and you must have inquired on the policy of the farmer, if they have good trackers, perhaps trained dogs, etc. If you shoot and there is blood on the scene, you must pay. Likewise if the carcass is only found the next day and there is not much left. It is the right of the farmer to refuse you any further hunting or even access to his land, if you do not follow this rule. Likewise, if you feel you were not treated well, it is your right to hunt elsewhere. And if you want to shoot an Oryx and the guide/PH or whoever is with you, say go, and it’s a sable antelope, you pay. If you respect these people, their animals and their rules, they will make it their responsibility to find your trophy. |

|

SABA requires as part of their proficiency program, for hunters to actively practice and partake in competitions. |

g) A female animal (cow, ewe or sow) is with dependent young. |

The target in the case of the spinal cord and brain is also protected by strong bones, creating a probability of not penetrating deep enough. In these cases where the animal was not killed it would lead to a wound. Therefore even though the shots would be perfectly effective, they are unethical as the chance of violating the death principle is too big. |

|

One of the biggest issues we just touched is marginal equipment. This subject is however so large, that it fills almost a whole proficiency program. |

4.12 Conclusion

Please take note that although these recommendations are based on hunting experiences, it does not guarantee a successful hunt. It also follows that it is possible to hunt successful, although usually not lawful/ethical, by not adhering to them. Currently the law prescribes some equipment requirements, but makes no mention of the archer's abilities. The equipment provides penetration, while the archer provides accuracy, and it is on this point that we base our recommendations. |

|

4.13 Some miscellaneous reading

| Further Reading: Engee Potgieter, AB&A, Aug 2007, p39, "Take better trophy photos" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Oct 2007, p15, "Building blinds for bowhunting" Louis Stoffberg, AB&A, Jun 2008, p55, "Bou 'n Gawe Skuiling" Harry Marx, AB&A, Jan 2009, p11, "The cheapest chronograph yet" Harry Marx, AB&A, Dec 2007, p19, "A 'cheap' Chronograph" Cleve Cheney, AB&A, Jun 2008, p20, "Bushcraft: Fire" |

5 Species

5.1 Species Categories

The use of species categories are no longer promoted, and instead we propose simply to work on the animal's mass. This allows for "relaxing" the requirements for young animals without worrying about arbitrary category borders.

However, as we introduced the effect of the broadhead into the requirements since the last edition, we will here provide tables for various broadheads. These tables are also available on the web at http://www.bowhunting.co.za/SABA/asp/minreq.asp |

The first table is for four bladed chisel point tips: |